A

Biological Paradise

A

Biological Paradise  A

Biological Paradise

A

Biological Paradise During the glacial period of 10,000 to 20,000 years ago, much of the northern part of North America was covered by a layer of ice as much as 2 miles thick. These glaciers did not reach the southern Appalachians, and this area became a haven for plant and animal species whose northern habitats were inundated by ice. Partly as a result and partly because of the great age of the mountains and the wide range of temperatures, there is a complex assemblage of plants and animals, including endemics and northern and southern species finding common ground here in the mountains.

The combination of the great age of the mountains, the absence of inundation by the northern glaciers, the high-elevation habitats, and the temperate climate results in a high diversity of flowering plants, plus the occurrence of many plants that are endemic and others that are northern plants occurring far south of their main range. Of the nearly 3,000 species of higher plants found in North Carolina, approximately 1,400 occur in the mountains. In addition, there are around 350 species of mosses and moss-allies and over 2,000 species of fungi.

Due to their abundance and variety, wildflowers of the Blue Ridge province are of particular interest to naturalists. From March through September, depending on your elevation, you can be treated to a spectacular display beginning on the forest floor and ending in roadside fields and openings throughout the summer. If you miss the peak of woodland wildflowers in April in Asheville, just travel upward a few thousand feet and see some of the same species blooming much later in the higher elevations.

Wildflower aficionados will want to search out southern Appalachian endemics such as galax (Galax urceolata), Michaux's saxifrage (Saxifraga michauxii), mountain wood shamrock (Oxalis montana), Vasey's trillium (Trillium vaseyi), mountain St. John's wort (Hypericum graveolens), and mountain krigia (Krigia montana). Luckily, there are a number of excellent wildflower field guides, including some specific to the Blue Ridge Parkway [Figs. 4,11,19,23,30] and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park [Fig. 44], which can help you in your search.

In addition to luxuriant plant growth resulting from a complex geologic past and suitable climate, the North Carolina mountains have always had an interesting, and in some cases unique, assemblage of animals. In historic times, now extirpated mammal species such as "mountain" bison (Bison bison), gray wolves (Canis lupus), and elk (Cervus elaphus) roamed here. But these species were quickly eliminated by the early European settlers.

Before the Civil War, few studies of animals, including the mammals, were made in the Appalachians. Within five years after the Civil War, however, a number of zoologists visited the area to do survey work. These included Edward Drinker Cope (he was famous for his work in paleozoology), William Brewster after whom the hybrid Brewster's warbler (Vermivora pinus x V. chrysoptera) is named, and John Simpson Cairns, a local ornithologist who accidentally shot and killed himself while collecting birds north of Balsam Gap. By the turn of the century, though, increasing numbers of zoologists had thoroughly explored the North Carolina mountainous area and produced a rich literature on its animals.

As with plants, animal populations vary according to elevation and the resulting climatic conditions. Red squirrels (Tamiascirus hudsonicus) and red-backed voles (Clethrionomys gapperi), for example, generally occur in the higher elevation red spruce-Fraser fir forests. At these higher elevations where there are rocky outcrops (talus slopes, for example), the eastern spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius) and long-tailed shrew (Sorex dispar) occur. At high elevations, too, one may find isolated populations of the northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) and rare water shrew (Sorex palustris), found only on Roan Mountain [Fig. 15], with small populations in the Great Smoky Mountains and near Mount Mitchell on Bald Knob.

On the balds, eastern voles (Scalopus aquaticus), meadow jumping mice (Zapus hudsonius), and least weasels (Mustela nivalis) occur, but at the lower elevation cove forests, different mammals are found: eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus), gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), black bears (Ursus americanus), and white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus). Still lower down the mountains in the oak-hickory woodlands are eastern cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus), striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), and Virginia opossums (Didelphus virginiana). Several mammal species occur within more than one life zone: eastern chipmunks, gray squirrels, white-tailed deer, black bears, and raccoons occur in both cove and oak-hickory forestlands. Along nearly any roadway occur woodchucks—Marmota monax, sometimes called groundhogs—which were rare during colonial times, but, like opossums and deer, have greatly increased in numbers as the forested land has been opened.

Although a rarity in these mountains, wherever caves occur, a variety of bats can be expected. Some species that occur here belong to one genus, myotis: the little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus), Keen's myotis (Myotis keenii), and the small-footed myotis (Myotis leibii). The Indiana myotis (Myotis sodalis) and Townsend's big-eared bat (Plecotus townsendii), like a number of our native species, are listed as threatened or endangered.

Although several of North Carolina's mammal species have been extirpated or nearly lost primarily because of habitat change and other factors, there are still approximately 67 fur-bearing species that occur in Western North Carolina.

Like mammals, birds are distributed in an altitudinal fashion. Northern saw-whet owls (Aegolius acadicus), common ravens (Corvus corax), and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) inhabit Mount Mitchell State Park, elevation 6.684 feet. Wood thrushes (Hylocichla mustelina), northern cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis), and the tufted titmouse (Parus bicolor) are common in Asheville, elevation 2,000 feet. Some overlap exists between the highest elevations and the cove forests, where such typically northern species of birds such as the dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis) and winter wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) overlap with the lower-elevation Carolina chickadee (Parus carolinensis) and red-eyed vireo (Vireo olivaceus). Several species of birds are extinct, including the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), which occurred here in the millions but was lost primarily due to overhunting and decline of the birds' habitat.

Fish,

amphibians, and reptiles, however, are much more tightly confined to restrictive

habitats. There are 86 species of fish that occur in the western portion of

North Carolina. Cold water with high oxygen content is required by trout, warmer

water for bass. Because of colder temperatures, excellent populations of trout

but relatively few bass inhabit North Carolina's mountain waters.

Fish,

amphibians, and reptiles, however, are much more tightly confined to restrictive

habitats. There are 86 species of fish that occur in the western portion of

North Carolina. Cold water with high oxygen content is required by trout, warmer

water for bass. Because of colder temperatures, excellent populations of trout

but relatively few bass inhabit North Carolina's mountain waters.

Yet the great variety of both game and nongame fish are of great interest to naturalists. Species that are largely restricted to Western North Carolina include the mountain brook lamprey (Ichthysomyzon greeleyi) and the American brook lamprey (Lampetra appendix); several minnows, including the central stoneroller (Campostoma anomalum); the blotched and potfin chub, (Hybopsis insignis and H. monacha); several species of shiners (Notropis spp.); as well as two species of dace, the blacknose (Rhinichthys atrataulus) and the longnose (R. cataractal). Several species of redhorse (Moxostoma spp.) and three genera of catfish (Pylodictis, Noturus, and Ictalurus) also occur in the region's warmer waters. Among the smaller panfish that are found here are the rock bass (Ambloplites repestris), the green sunfish (Lepomis cyanellus), the redbreast sunfish, (L. auritus), the bluegill (L. macrochirus), the pumpkinseed (L. gibbosus), and the redear sunfish (L. microlophus). A few mountain localities have the yellow perch (Perca flavescens). The small and colorful darters (Percina spp.) number over a dozen species in the Blue Ridge. Even walleyes (Stizostedion vitreum), saugers (S. canadense), and the freshwater drum (Aplodinotus grunniens) occur in a few fairly restricted localities, and there are at least three species of sculpins (Cottus spp.) found in the area.

Reptiles, unlike most mountain fish, require a relatively warm environment and therefore are rare at higher elevations. Yet Western North Carolina has 11 species of turtles, 9 different lizards, and 23 species of snakes. Only the copperhead (Agkistroden contortrix) and timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) are poisonous; the copperhead, 24 to 45 inches in length, is the most common, living at elevations of up to nearly 3,000 feet in the mountains.

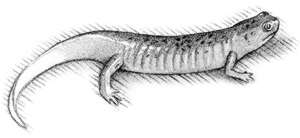

There is a wide variety of amphibians in Western North Carolina. Of these, over 50 different kinds of salamanders and related species and 14 species of frogs and toads occur in mountainous part of the state. Salamanders are more varied in Western North Carolina than any place in the world, and scientists from all over the world study them.

In addition to the great variety of salamanders, a variety of invertebrates, both aquatic and terrestrial, occur in the Blue Ridge province. Several hundred species of spiders are represented, as are a variety of crayfish and mollusks. The latter have over 100 terrestrial forms (snails); fewer are found in the mountain streams and stream impoundments. Throughout the western Appalachians there are approximately 23 freshwater clam varieties. Interestingly, 20 of these are fairly restricted to the Tennessee River system in North Carolina.

These bivalve mollusks have a very long life span, some having been known to live from 30 to 130 years. The ages of clams, like trees, can be determined from annular growth rings. Such growth patterns also reflect water quality and even the presence of heavy metals and other pollutants in our freshwater habitats. In addition to pollutants, though, the impoundment of many freshwater streams, resulting in deeper, cooler water, has had a deleterious effect on several mollusk species that prefer shallow riffle areas. The same habitat interference has undoubtedly decreased the number of native crayfish in several localities. Yet, there is still a good number of both mollusk and crayfish species in Blue Ridge waters.

These mountains also have a great variety of insects and, luckily for hikers and outdoor enthusiasts, few that bite. Most noticeable along woodland trails are assorted species of butterflies. The large and colorful Eastern tiger swallowtails (Papilio glaucus) are found everywhere in woodland settings but mostly along roadways, trails, and other forest openings. In the fall the North Carolina mountains are visited by thousands of migrating monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus), passing through on their 2,000-mile trek to central Mexico where they overwinter. An autumn field, especially one containing goldenrod (Solidago spp.) and asters (Aster spp.), is an ideal place to view monarch butterflies. A well-known viewing spot during their fall migration is the Cherry Cove Overlook south of Mount Pisgah on the Blue Ridge Parkway. Thousands of migrating monarchs are sometimes seen there making their way through the mountain ridges.