Headquarters for the Tellico Ranger District is about 5 miles east of Tellico Plains just off the Cherohala Skyway on Forest Road (FR) 210, which runs along the Tellico River. Nestled at the end of a Forest Road (look for the headquarters sign) in an idyllic setting is a historic CCC complex converted into offices for this district. This is a good starting point for gathering information about the area. Friendly personnel, maps, brochures, and books will make your visit more rewarding.

The Cherohala Skyway, a 52-mile scenic highway, connects Tellico Plains, Tennessee with Robbinsville, North Carolina. "Cherohala" is a combination of the names of the two national forests—the Cherokee and Nantahala—that the highway links. The skyway, one of only 20 Federal Highway Administration Scenic Byways in the nation, begins at an elevation of 900 feet just east of Tellico Plains and follows the Tellico River gorge for 5 miles. Then it rises with the Unaka Mountains to an elevation of 5,390 feet at Santeetlah Gap before descending toward Robbinsville. Twenty-two miles east of Tellico Plains is the highest major bridge in the southeastern United States. It is 700 feet long at an elevation of 4,000 feet. The 26-mile mark is near where the Trail of Tears that forced thousands of Cherokee Indians to Oklahoma began.

The Tellico Ranger District contains 123,372 acres in Monroe County with its highest peak, Haw Knob, reaching 5,472 feet above sea level. Although there are many undeveloped areas available for camping, there are eight developed campgrounds. Hikers may trek 150 miles on 29 trails, and equestrians have access to 31 miles along 8 trails. If touring by automobile is more appealing, the Cherohala Skyway is a unique drive providing many grand vistas with parking at prominent overlooks. The Tellico River Road (FR 210), North River Road (FR 217), and Citico Creek Road (FR 35) are the other popular scenic routes.

Be sure to take your camera and plenty of film to capture the spectacular scenes from river bottom to mountaintops. Some of the best places to shoot on the Cherohala Skyway are Lake View in Tennessee, and Sugar Cove and Hooper Bald in North Carolina. A 200mm lens or larger will help bring the distant mountains and valleys closer for a deeper appreciation later.

Bald River Falls will also make you glad you had a camera. Here is a good place to try different filters for special effects and to use different shutter speeds to create a milky, silky effect with the falling water. Early morning would be the time to snap a misty shot.

Anglers enjoy 38 miles of stocked rainbow and brown trout waters with 19 miles

managed for brook trout. Indian Boundary Lake offers 96 acres of warm-water

fishing, with species including blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus), largemouth

bass (Micropterus salmoides), smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu),

bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), and redbreasted sunfish (Lepomis

auritus).

Hunters of big and small game are welcomed in the Tellico Ranger District. About 50 permanent forest openings are maintained for wildlife. Bear, boar, deer, turkey, grouse, squirrel, and raccoon are the sought-after species. The boar are reported to have been imported from the German Hartz Mountains to stock a preserve in North Carolina—but they didn't stay there. Today they are referred to as Russian, or "Rooshian" boar, and the escapees' descendants populate these mountains.

The seepage salamander (Desmognathus aeneus), masked shrew (Sorex cinereus), star-nosed mole (Conylura cristata), ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), huckleberry (Gaylussacia ursina), and hedge nettle (Stachys sp.) are a few other animals and plants found in the Tellico District.

No complete botanical surveys have been conducted, but some areas have been studied. Citico Creek Wilderness Area has 536 vascular plant species and 70 species of trees. Vascular plants include most flowering plants, conifers, ferns, and club mosses.

Today's forests in the Tellico Ranger District are thought to closely resemble ancient ones consisting of cove hardwoods in coves or valleys below 4,500 feet elevation. Dominant species include yellow-poplar, yellow birch, Eastern hemlock, silverbells, buckeye, basswood, sugar maple, Southern yellow pine, and white pine. Doghobble (Leucothoe axillaris), rhododendron, wild hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens), and strawberry bush (Euonymus americanus) are shrubs found in the understory.

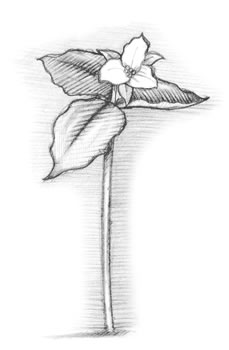

The Tellico Ranger District contains many of the spring wildflowers found throughout the Unaka Mountains. Blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides), squirrelcorn (Dicentra canadensis), umbrella-leaf, (Diphylleia cymosa) sharp-lobed hepatica (Hepatica acutiloba), bishop's cap (Mitella diphylla), and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) are among these.

About 19 percent (23,659 acres) of the Tellico Ranger District is in the National Wilderness Preservation System to maintain naturalness and solitude. While hiking, camping, hunting, fishing, and riding horses (in designated areas) is allowed, no motorized vehicles or equipment, bicycles, or other wheeled carriers are.

[Fig. 36] Originating in the Snowbird Mountains of North Carolina, the Tellico River drains a watershed of 285 square miles, taking its water 53 miles to the Little Tennessee River at Tellico Lake. Many streams feed the river, with Sycamore Creek, North River, and Bald River among the major contributors. There are many especially scenic views along the river.

When the water is low in the Tellico River it is not suitable for navigation within the Tellico Ranger District, but when the water is high, it provides canoeists and kayakers ample opportunity to run the river and be challenged by rapids up to Class V.

Rivers were historically used as routes through the rough mountain terrain. The Tellico River was in use as a corridor for at least 12,000 years. Native Americans used this area, the te-li-quo, which is Cherokee for plains, for hunting game and gathering food. For the last 2,000 years it served for agriculture.

The Tellico River is lined with sites showing signs of use by Indians. Cherokee Indians lived and farmed the land along the river until 1819 when a boundary was established giving whites the land downstream from river-mile 34. The two groups lived together until 1838 when the Cherokee were forced by the whites to move to Oklahoma.

With more land opened to the settlers, they began subsistence farming, harvesting some timber, and raising livestock on the open range. Cattle, pigs, and sheep grazed on land after it was cleared by fire and grasses grew there. Remnants of old farmsteads can be found throughout the area today.

After the Civil War, the Tellico River area became the target of timber companies. Babcock Timber Company acquired the area and hauled out timber from the late 1800s until the late 1920s. Remnants of the logging operation exist today. In fact, FR 120—the Tellico River Road—was one of the logging railroad beds. Some old splash dams can be found along the river.

After the denuding of the forests, erosion became a serious problem. The Weeks

Act of 1911 gave the federal government authority to purchase private lands

east of the Mississippi River and establish national forests in the region

to manage the natural resources of the southern Appalachian Mountains. The

Tellico River area was only one small area that suffered over-logging and erosion.

In 1920, the Tellico River corridor became part of the Cherokee National Forest and the Nantahala National Forest. Within a decade the area was ironically blessed by the Great Depression. Civilian Conservation Corps members found work all along the Tellico River, and, like the Indians before them, their work is evident today. One of the CCC efforts still functioning is the Tellico Ranger Station, which was the first CCC camp constructed in Tennessee and among the first 50 built in the United States.

The Forest Service has managed, maintained, and improved the Tellico Ranger District since taking over in the 1920s.

[Fig. 36(9)] According to legend, a man named Hughes built a one-room cabin in this remote part of the South during the 1860s to hide from being asked to be a soldier in the Civil War. After the war, there was an addition to the one-room cabin. Construction continued until its log style included Swiss, German, and English designs. The fireplace is the oldest part of the cabin.

Jack Donley purchased the cabin and some adjacent land after the war. The pioneer became fairly well known: Donley Mountain and Donley Branch bear his name. He lived until 1941, and his descendants maintained possession of the cabin until 1994.

Today, the pioneer cabin is restored, and it can be rented for a three-night maximum through the Tellico Ranger District.

[Fig. 36(6)] The Tellico Ranger District contains three wilderness areas: the Joyce Kilmer/Slickrock Wilderness designated in 1975, and the Citico Creek Wilderness and the Bald River Gorge Wilderness designated in 1984.

Citico Creek Wilderness Area is north of the Cherohala Skyway on the North Carolina border. Fodderstack Trail (#95) runs from the north at Salt Spring Mountain south to and along the Tennessee/North Carolina border, forming the dividing line between the Joyce Kilmer/Slickrock Wilderness Area and Citico Creek Wilderness Area. The Unicoi Mountains and steep ridges running along Citico Creek Wilderness Area's western side create steep slopes with rugged terrain covered in oaks and pine.

Citico Creek Wilderness Area, 16,226 acres in Monroe County, is the largest wilderness area in the CNF with about 58 miles of trails. Citico, derived from the Cherokee word sitiku, means "a place of clean fishing water."

The timber in this area was cut in the early 1900s except for about 400 acres of hemlock and hardwoods in the Jefferys Hell section in the southern end of Citico Creek Wilderness Area. A fire, in 1925, destroyed half of what would later become the Citico Creek Wilderness area, many of the structures needed to harvest timber, and the timber-carrying railroad. The operation was deemed too expensive to reconstruct for the remaining, nearly unreachable 400 acres. Today hikers can take Falls Branch Trail (#87) and Jefferys Hell Trail (#196) for a walk through the old-growth forest of hemlock and poplar.

Jefferys Hell was named, as one story has it, for a man who went looking for his lost dogs and became lost himself. The story doesn't say if he found his dogs, but it claims he lost his life. Legend has it that before he went into the dense rhododendron and mountain laurel growth he said, "I'll find them if I have to go to hell for them."

Another account is that Jeffery wandered from camp among the uninhabited wild mountains of steep cliffs, ravines, and dense, tangled growths of rhododendron and doghobble. After two days without food, he came out at the headwaters of the Tellico River and was asked where he had been. His answer was, "I don't know, but I have been in hell."

[Fig. 36(10)] The Falls Branch Trail (#87), a short, easy hike, leads to the 80-foot waterfall on Falls Branch at the southern end of Citico Wilderness Area. This scenic trail runs north from the Cherohala Skyway at Rattlesnake Rock parking lot. This trail is marked at the western end of the parking lot. The trail passes through the old-growth hemlock and hardwoods saved by the fire of 1925. A springtime hike will treat you to blooming wildflowers.

The trail follows the stream down to the falls. There are several good views

of the falls, but do not climb them. They are slick with moss and dangerous.

This is considered one of the prettiest waterfalls in the southern CNF, dropping about 30 feet, cascading down a large escarpment for several feet, then plummeting about 30 feet more in a horsetail shape. The falls looks like angel hair when the flow is light but is dramatic when the flow is heavy.

[Fig. 36(4)] The Fodderstack Trail (#95), the longest trail in the area, runs along the divide between the Citico Creek Wilderness Area and the Joyce Kilmer/Slickrock Wilderness Area, and gives hikers access to other trails into both wildernesses. Beginning at Farr Gap where you can see into the Joyce Kilmer/Slickrock Wilderness Area, the hike passes close to the Little Fodderstack, the Big Fodderstack, and the Rockstack. These three rises offer good views, but the best view of the countryside is from Bob Stratton Bald in North Carolina via the Stratton Bald Trail (#54), which leads east where the Fodderstack Trail heads southwest at the southern edge of the wilderness area. The hike is 0.4 mile.

The Bob Stratton Bald rises to 5,261 feet with views of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park to the north and the Slickrock Creek valley. Campsites in the grass and spring water on the southeastern side make this an excellent resting spot before returning to the Fodderstack Trail and finishing the hike to Cold Spring Gap on the Cherohala Skyway.

Fodderstack is also a horse trail with several campsites but no potable water. Horses can drink form several streams.

[Fig. 36(1), Fig. 37] The Joyce Kilmer/Slickrock Wilderness Area contains 17,013 total acres in Tennessee and North Carolina with 3,881 acres in the Tellico District. The Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest within the Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina is a 3,840-acre preserve named for the poet who wrote "Trees." A well-worn trail from the trailhead shelter, which has the poem framed on one of its walls, leads through trees 400 years old, 150 feet tall, and 20 feet around.

Kilmer, killed in 1918 during a World War I reconnaissance mission in France, wrote his famous poem about the white oak trees on the campus of Rutgers College, which he attended from 1904 to 1906. Veterans of Foreign Wars asked the federal government for a memorial to Kilmer. This led to the Forest Service being asked to locate a section of virgin forest to fulfill the veterans' wish.

In 1935, such a tract was located but the price was high—seven times more than the going rate. At $28 per acre, 13,055 acres were purchased from Gennett Lumber Company in Little Santeetlah basin. The virgin forest had been spared the saw because the Lakes Calderwood and Santeetlah flooded the railroad tracks used to haul out trees. The timber company went bankrupt before another way to move the logs was ready. As fire saved some trees in the Citico Creek Wilderness Area, water saved the trees that became a tribute to the poet and Croix de Guerre soldier on July 30, 1936, exactly 18 years after his death.

[Fig. 36(3), Fig. 37(3)] The Joyce Kilmer National Recreation Trail offers two loops (shaped like a figure eight) through the forest. The loop nearer the parking lot is 1.25 miles long and the upper trail is 0.75 mile long. Pay attention to the warning about falling limbs, called widow-makers. Poplar trees typically lose their lower limbs and some of the old trees are dying. Clearing them is prohibited. Also note the large rock with a plaque honoring Kilmer located across the trail from the shelter.

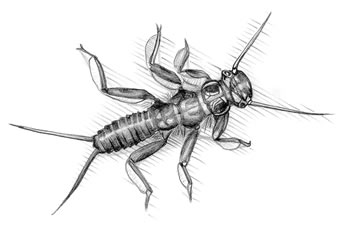

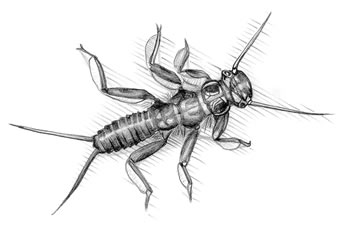

Along the trail, in addition to the huge poplar and hemlocks, are red maple, beech, red oak, yellow birch, and Carolina silverbell (Halesia carolina). Wildflowers include trilliums, violets, galax, crested dwarf iris (Iris cristata), and jack-in-the-pulpit among the nearly ubiquitous ferns. Wildlife is same as in the CNF but songbirds love these woods. Wood thrushes (Hylocichla musteline) supply one of the prettiest songs in the forest. Other songs come from ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapillus), golden-crowned kinglets (Regulus satrapa), brown creepers (Certhia familiaris), and scarlet tanagers (Piranga olivacea).

There are three notable camping areas in the Tellico District and several smaller ones. The three detailed here are unique among all the camping grounds, providing more activities and facilities.

[Fig. 36(5)] The Indian Boundary Recreation Area is the largest and most popular campground in this district. The Indian Boundary Lake is the focal point of the campground during the summer when it is open for swimming. The lake is open to fishing all year but no gasoline motors are allowed to operate in the lake. Hikers use the campground as a base camp to take advantage of nearby trails.

[Fig. 36(2)] Jakes Best Campground is north of Indian Boundary Lake on FR 35-1 (Citico Creek Road). This is a pack-it-in, pack-it-out area with trailer space but no electricity. This place attracts anglers, hunters, and hikers.

[Fig. 41(4)] Young Branch Horse Camp is the northernmost camping area in the Tellico District. This unique campground is restricted to people with saddle, pack, and draft animals. There are special regulations for this area, and there is space for 25 animals and 35 people (seven campsites hold a maximum of five people each).

[Fig. 36(14)] It is listed on maps as the Pheasant Field Fish Hatchery, but its present name is the Tellico Hatchery. It is located on FR 210 at Sycamore Creek.

Originally this was a trout-rearing station, not a hatchery, built by the CCC between 1939 and 1941 with six circular pools inside a frame house. In the 1940s six raceways were added. In the 1960s the rearing station grew to become a hatchery. The raceways were rebuilt with the addition of a work station, a manager's residence, and a line of 16 raceways and earthen pools.

In 1991 it became a hatchery for southern and northern strains of brook trout and brown trout. The fish, about 9 inches long, come from the Dale Hollow Hatchery and are intensively managed for stocking in local waters: 12 miles of the Tellico River, 6 miles of the Citico Creek, a handicapped-accessible facility called Green Cove Pond, and a few small streams in Polk County. In 1991 the 16 raceways and earthen pools were removed and replaced with 28 modern raceways.

There is some natural reproduction of trout in the stocked waters but not enough to keep up with demand. All the trout streams are put-and-take. A daily permit helps fund the stocking program.

Southern brook trout restoration is in the research stage here. The upper end of Sycamore Creek was stocked with brook trout, and heavy rains washed some down among the browns and rainbows stocked several years ago in the lower section. Studies are under way to see how the less-competitive brook trout fares among the other trout.

[Fig. 36(8)] The Bald River Gorge Wilderness Area (3,887 acres) lies between FR 210 to the north and FR 126 to the south. The Basin Lead marks the eastern boundary but there is no discernible landmark denoting the western boundary. The gorge has steep slopes; clean, cold-water streams containing trout; beautiful wildflower displays in spring; gorgeous colored leaves in fall; and small and big game, as well as wildlife typical in the CNF.

The wilderness area, as in most sections of the Tellico Ranger District, was logged in the 1920s but experienced less agricultural use. Subsistence farming may have been conducted here before timber companies bought the land, but evidence is difficult to find, except at the head of Brookshire Creek near the North Carolina border.

Some logging continued into the 1960s, and during the 1980s clear-cut logging occurred south of Henderson Top near Maple Camp Lead and at the head of Bald River. Conservationists fought a long time to have the Bald River watershed protected. It took until 1984 to get the Bald River Gorge area protected, but today it is safe from logging.

[Fig. 36(12)] Only one trail completely traverses the Bald River Wilderness Area, the Bald River Trail (#88). The Bald River Trail follows the Bald River upstream through a deciduous forest with some white pine, hemlock, doghobble, mountain laurel, and rhododendron. Along the trail are small camping areas, which see heavy use from spring through the fall. There are some nice views of the river and one good view of a large cascade. Cantrell parking area on FR 126 is the end of the trail.

[Fig. 36(11)] The Bald River Falls, lauded as the most impressive waterfall in eastern Tennessee and accessible by automobile, tumbles about 90 feet into a small plunge pool. This very attractive waterfall attracts so many visitors and photographers it may be difficult to find a parking space.

The waterfall is segmented, cascading across the wide rock rim, and then becoming a single stream before reaching the bottom. There is an excellent view from the nearby bridge.

[Fig. 36(13)] Before the settlers came, the Cherokee used the Warrior's Passage Trail. As with most trails, it was probably a game trail that Indians used, and through the years it became part of their road system connecting tribes and hunting grounds. White settlers and British soldiers improved the road and built a bridge over the Tellico River. This trail connected with Fort Loudoun on the Little Tennessee River in the mid-1700s. Once a trail through the southern Appalachian Mountains, today a small 5-mile section remains in the Tellico Ranger District and is protected under the 1988 CNF Management Plan.

The trail is difficult to follow in places because blazes are sometimes hard to find and the trail is not maintained.

The prominent feature 0.8 mile off the trail on Waucheesi Mountain Road (FR 126C) is the Waucheesi tower at an elevation of 3,692 feet. Once a fire tower, it is now a microwave relay station. From this high point, you have a spectacular 360-degree view with the Bald River Gorge Wilderness to the northeast.