The Okefenokee Swamp

[Fig. 23] If you fly

across Georgia and look down on the landscape, it appears that almost every

acre of the state is under some kind of development. Roads, towns, cleared patches

of farmland, and rows upon rows of pine trees seem to fill every available patch

of land. Then, at the last minute before arriving at the coast, you look down

and it appears the hand of man has been stayed: Below you are 700 square miles

of wet, green wilderness, known as the Okefenokee Swamp, the largest peat producing

bog swamp in North America.

A national treasure, the vast and mysterious Okefenokee Swamp provides refuge

for a large number of animals and plants that thrive in the solitude of the

lakes, islands, wetlands, and uplands that make up the sanctuary. As one of

the largest and most significant wetland complexes in the United States, the

Okefenokee has its own peculiar mix of natural environments, wildlife, and human

mythology. Visitors to the swamp can hear the prehistoric bellow of ancient

reptiles, the raucous call of the sandhill crane, and the garrulous chorus of

frogs in spring. The natural setting is a strange and beautiful mosaic, from

a maze of towering cypresses growing out of the mirrorlike waters in some areas

of the swamp to vast prairie grasslands in other sections.

Visiting

the swamp can be somewhat confusing. There is no one park you go to that offers

the entirety of the Okefenokee experience. Visitors have four choices of parks,

each with their own set of natural qualities and recreation opportunities. Three

parks are located on the eastern side of the swamp, and one park is located

on the southwestern side. Because of the size of the swamp, visiting the full

complement of parks requires some driving because one must travel around the

perimeter of the wetland, which is larger than the interior of Interstate 285

or all the barrier islands of Georgia combined. The most popular activities

in the swamp are sightseeing, boating, and fishing.

Visiting

the swamp can be somewhat confusing. There is no one park you go to that offers

the entirety of the Okefenokee experience. Visitors have four choices of parks,

each with their own set of natural qualities and recreation opportunities. Three

parks are located on the eastern side of the swamp, and one park is located

on the southwestern side. Because of the size of the swamp, visiting the full

complement of parks requires some driving because one must travel around the

perimeter of the wetland, which is larger than the interior of Interstate 285

or all the barrier islands of Georgia combined. The most popular activities

in the swamp are sightseeing, boating, and fishing.

On the southwestern side near Fargo is Stephen C. Foster State Park, which marks

the headwaters of the Suwannee River and is popular for its cypress swamps and

fishing. North of the swamp near Waycross is Laura S. Walker State Park, which

comprises the natural communities that are characteristic of the swamp's margin.

Not quite the swamp experience that some may expect, it nonetheless offers picnicking,

camping, golfing, and a lake for water recreation. West of the park and south

of Waycross is the Okefenokee Swamp Park, which is geared for the visitor who

would rather see alligators, snakes, and bears in captivity rather than search

them out in the wilds. This is a quick and easy way to see the typical environments

and wildlife of the swamp without investing too much trouble or time. Farther

south near Folkston is Suwannee Canal Recreation Area, a Federal park near that

failed venture that today provides water access to the more typical prairie

environment of the swamp. Highlights here are nature boardwalks, historic sites,

fishing, boating, and nature observation. Other attractions around the swamp

include a large hunting area and two museums dedicated to the swamp's historical

and natural heritage. Full details on these attractions follow.

The

Okefenokee Swamp's Natural Features

The

Okefenokee Swamp's Natural Features

In the 1770s, naturalist William Bartram correctly observed that the swamp was

a "terrestrial paradise" and "great source of rivers" and

that Creek Indians considered the "Ouaquaphenogaw" a "most blissful

spot of the earth." In 1902, naturalist Roland M. Harper wrote that the

swamp "must be seen to be appreciated…there is nothing else exactly

like it in the world." In modern times, photographs of the swamp taken

by satellite far above the earth show it as an obviously distinct greenish-yellow

shape in the southeastern corner of the state.

What the Indians appreciated long before European naturalists and high tech

spacecraft is that the Okefenokee is a very unusual and special ecosystem. Unfortunately,

for many years swamps were not prized by colonizing Europeans, who believed

them to be wastelands that need to be drained, cut out, and planted with crops.

Today we know better, but much of the general public still has a negative image

of swamplands as dark, scary jungles where evil lurks. Nothing could be further

from the truth.

The Okefenokee Swamp is a vast mosaic of natural communities, some looking like

the stereotypical cypress swamp, and others looking more like a treeless prairie

of wet grass. From aerial photography, scientists have identified approximately

20 different major habitat types that form the patchwork known as the Okefenokee.

Much of the swamp has never been visited by man.

The dimensions of the swamp are huge. While scientists debate its actual boundaries,

most agree that its watershed is more than 1,400 square miles and the swamp

is roughly 700 square miles, including wetlands in Florida. The national wildlife

refuge is 396,315 acres of which (912) 353,981 acres are part of the wilderness

preservation system. Rainfall—50 inches a year—supplies 70 to 90 percent

of the water in the swamp, with some small springs adding to the total. Depth

of the water ranges from 2 to 9 feet. Water drains in from the northwestern

side of the swamp and collects in a 435,000-acre basin. Eighty-five percent

of the water flowing out of the swamp is carried by the Suwannee River, which

rolls to the Gulf coast, and the remainder is carried by the St. Marys River

to the Atlantic coast. While water is a main element of the Okefenokee, only

1,000 acres of the swamp are open water areas, consisting of some 60 lakes,

gator holes, and watercourses.

Geologically,

the swamp is a newborn, with the oldest peat estimated to be 8,000 years old.

Approximately 200,000 years ago, the Atlantic Ocean covered the swamp. As the

climate cooled during subsequent ice ages, sea level dropped, and as the seas

receded, high dunes formed at various shorelines. Around 140,000 years ago,

a giant dune line known as Trail Ridge was formed, stretching from Starke, Florida

to Jesup, Georgia. This ridge, which makes up the eastern edge of the swamp,

acted as a dam to southeastern flowing rivers, causing water to pool behind

the ridge or flow around it to gaps in the ridge. The Satilla River flows through

one such gap, while the St. Marys River is forced south before reaching a gap,

where it moves east then north and east to the Atlantic Ocean.

Geologically,

the swamp is a newborn, with the oldest peat estimated to be 8,000 years old.

Approximately 200,000 years ago, the Atlantic Ocean covered the swamp. As the

climate cooled during subsequent ice ages, sea level dropped, and as the seas

receded, high dunes formed at various shorelines. Around 140,000 years ago,

a giant dune line known as Trail Ridge was formed, stretching from Starke, Florida

to Jesup, Georgia. This ridge, which makes up the eastern edge of the swamp,

acted as a dam to southeastern flowing rivers, causing water to pool behind

the ridge or flow around it to gaps in the ridge. The Satilla River flows through

one such gap, while the St. Marys River is forced south before reaching a gap,

where it moves east then north and east to the Atlantic Ocean.

Underlying the Okefenokee is a saucer-shaped basin with a firm sand floor that

is elevated between 128 and 103 feet above sea level. The top layer of sand

is from the Pleistocene Age only 2 million years ago. Below these sands at depths

ranging form 30 to 110 feet are 6-million-year old sands of the Pliocene epoch.

On top of the sand floor is a bed of peat that ranges from a thin layer to more

than 20 feet in depth. The peat gives the swamp much of its character; its name,

much of its landscape, and its unique water. The word Okefenokee is an Indian

word translated to mean "land of the trembling earth." The swamp produces

vegetation faster than it can decay. As vegetation dies and sinks, it slowly

decomposes, producing methane gas. When enough gas is produced, peat mats will

break away from the bottom and float to the water's surface in what is called

a blowup. Plants will colonize this blowup, creating a new entity called a battery.

Eventually, larger and sturdier trees become established on the battery giving

birth to an island. Walking on these batteries and islands, which may be floating,

is literally and figuratively like walking on a waterbed. Hence the name "land

of the trembling earth."

The peat, when mixed with fresh water, creates the acidic, tea-colored, reflective

waters of the Okefenokee that are internationally famous. With a pH of 3.7 (a

neutral pH is 7, with higher values alkaline), the chemistry of the water affects

every living form in the swamp. It is also delicious to drink, and sailing ships

used to go out of their way to fill their stores with the waters from the St.

Marys River, which would remain fresh during long journeys.

Floral communities of the swamp consist of pine uplands; forested wetlands of

bay, cypress, and blackgum; scrub-shrub wetlands; and mixed aquatic bed and

emergent wetland natural habitats. The ecosystem is fire dependent, with a high

lightning frequency. Fires generally burn lightly, considering the wet nature

of the swamp. Natural succession here goes from prairie, to cypress swamp, and

finally to blackgum or bay swamp. Fire prevents the last stage from happening,

keeping the swamp at the cypress stage as cypress is fire-tolerant but blackgum

and bays, normally understory trees, are not. Dry peat is very combustible.

When vast forests of cypress were cut out from the swamp— 425 million board

feet—in the first third of the 1900s, bay and blackgum shot up to replace

the cypress trees. The building of a dam near Stephen C. Foster State Park has

kept the swamp unusually wet, which has affected the frequency and strength

of fires in the swamp in ways still not totally understood.

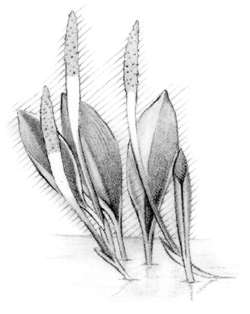

Today,

the swamp has roughtly 70 tree islands that make up 10 percent of the swamp.

The signature cypress forest occupies around 25 percent. Approximately 20 percent

of the swamp is prairie, consisting of grasses and sedges, moss, ferns, and

rushes. Emergent plants such as golden club, pickerelweed, and yellow-eyed grass

are characteristic plants of the prairie. Blue flag irises add splashes of lavender.

And roughly 33 percent of the swamp is scrub-shrub, with evergreen, leathery

leafed shrubs such as dahoon holly and fetterbush dominating the landscape.

The rest of the swamp is mixed pine uplands.

Today,

the swamp has roughtly 70 tree islands that make up 10 percent of the swamp.

The signature cypress forest occupies around 25 percent. Approximately 20 percent

of the swamp is prairie, consisting of grasses and sedges, moss, ferns, and

rushes. Emergent plants such as golden club, pickerelweed, and yellow-eyed grass

are characteristic plants of the prairie. Blue flag irises add splashes of lavender.

And roughly 33 percent of the swamp is scrub-shrub, with evergreen, leathery

leafed shrubs such as dahoon holly and fetterbush dominating the landscape.

The rest of the swamp is mixed pine uplands.

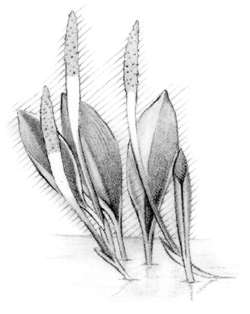

One fascinating aspect of the Okefenokee's flora are the carnivorous plants

that have adapted to the swamp's low nitrogen and phosphorus content. Carnivorous

plants have evolved the skill of surviving in nutrient-poor conditions by luring,

trapping, and digesting animals. This specialization gives them the advantage

of living in impoverished areas with little crowding from other plants. In the

swamp, beautiful hooded pitcher plants (Sarracenia minor), golden trumpets

(Sarracenia flava), sundews (Drosera intermedia), and bladderworts

(Utricularia purpurea) use varying strategies for finding meals.

Because the swamp is young, the diversity of its flora and fauna is relatively

low and no endemics have been found—no Okefenokee pocket gopher. However,

many species thrive because it is such an immense refuge with an absence of

roads, providing sanctuary not found in smaller parks. Identified in the refuge

have been (912) 232 species of birds, 42 species of mammals, 58 species of reptiles,

32 species of amphibians, and 34 species of fishes.

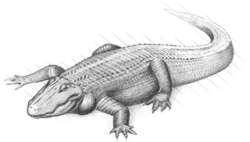

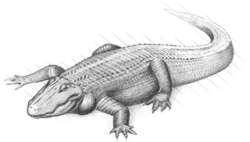

Some particular fauna of the swamp should be mentioned. Of course alligators

and snakes are the two most feared animals associated with the swamp. Okefenokee's

alligator population has rebounded since the animal received federal protection

in the 1970s, and today about 12,000 alligators make their home here, a conservation

success story. Their bellows in spring may be the most remarkable sound made

by a North American animal. With 36 species of snakes, 5 of them poisonous,

the swamp is serpent heaven. The most common poisonous snake is the water-loving

cottonmouth. Other venomous snakes include the Eastern diamondback, pygmy rattler,

canebrake rattler, and coral snake. The likelihood of getting bitten by a snake

is greatly overrated, with the vast majority of snakebites occurring as a consequence

of people picking up snakes. Nonetheless, they can be deadly so visitors should

avoid disturbing them.

Maybe the most beautiful snake of the swamp is the rare rainbow snake, which

has an iridescent black body with red stripes running its length and brilliant

yellow along its lower sides. Also found in the swamp is the federally threatened

Eastern indigo snake, the longest native snake in the U.S. growing to more than

8 feet.

Florida naturalist Archie Carr wrote that there are only three great animal

voices remaining in the southeastern U.S.: the "jovial lunacy of the barred

owl…the roar of the alligator…(and) the ethereal bugling of the sandhill

crane." All three are heard in the swamp and all three will stop you in

your tracks. Certainly the dinosaur rumble of the alligator can be imagined,

as can the hoot of an owl, but the voice of the "watchman of the swamp"

is unlike anything you've ever heard. Sandhills are the largest birds in the

swamp, standing 4 feet tall with a 7-foot wingspan, and they have a cypress

gray body and red forehead. They mate for life and nest in open places where

trees do not block their keen vision.

Approximately 30 warblers have been identified in the swamp, including the prothonotary

warbler (Protonotaria citrea), a bird that is characteristic of southern

swamplands, where its bright, golden-orange plumage is conspicuous in the dark

cypress swamps. It nests in the refuge and has a loud ringing "sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet"

song.

Many species of waterfowl use the wet areas during the winter, including mallards,

ring-necked ducks, wood ducks, black ducks, coots, green-winged teal, and mergansers.

Anhingas are a common sight, perched on a stump with their wings outstretched.

The water turkey, as it's also called, swims in the water preying on fish, and

then must dry its wings before it can fly.

The most commonly observed white wading bird in the swamp is the white ibis

(Eudociums albus), with its orange curved bill and orange legs, but many

other wading birds can be seen including herons, egrets, and wood storks. Osprey,

hawks, vultures, and eagles are soar the skies looking for food. In the woodlands,

wild turkeys, owls, and red-headed and red-cockaded woodpeckers make their homes.

Adding to the sounds of the swamp are the more than 20 frog and toad species,

each with its distinctive song. On a rainy summer night, visitors may hear up

to 12 different frog species singing their particular songs.

The more commonly seen of the 50 mammals of the swamp are white-tailed deer,

foxes, feral hogs, raccoons, and armadillos. Nine species of bats can be observed

eating insects as the sun goes down. Round-tailed muskrats are common in the

prairies. Bobcats are widespread and plentiful, but very shy. Floyds Island

is a great place to see a bobcat. Otters are more frequently seen in colder

months when alligators are less active. Of special mention is the largest mammal

of the swamp, the Florida black bear (Ursus americanus floridianus).

This subspecies, called a "hog bear" and smaller than the bears found

in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, weighs approximately 150 pounds

and numbers around 500 animals. They are hunted during a six-day period once

a year.

The insect life of the swamp is fascinating and plays an important role in nutrient

cycling. Scientists have estimated that 12 to 40 percent of the forest canopy

is consumed by insects, primarily butterflies and moths. Hordes of iridescent

and harmless dragonflies are seen perched on tree trunks, warming themselves

in the sun's rays. On the lily pads are fishing spiders (Dolomedes),

which do not spin webs to capture prey but eat insects that have fallen into

the water. The beautiful, orb-weaving golden-silk spider (Nephila clavipes)

females have golden bodies and legs with conspicuous tufts of black hair on

the first and last pair of legs. The male is small and drab colored. Large colonies

of these spiders can be found in shaded woodlands near watercourses.

The

Okefenokee Swamp's Human History

The

Okefenokee Swamp's Human History

Shell middens found in the swamp are evidence of Indian activities in the Okefenokee,

where the earliest artifacts date back 4,000 years. The earliest record of European

inhabitation of the swamp shows it occurred from 1620–1656 when the Spanish

established a mission named Santiago de Oconi at the headwaters of the St. Marys

River.

When naturalist William Bartram traveled in the swamp in the 1770s, he recorded

an old Indian legend he heard about the swamp. A band of Indians, hunting in

the swamp, had seen a "terrestrial paradise" on the banks of an enchanted

island surrounded by a beautiful lake, and as they tried to reach it, they only

became lost in the confusing labyrinth of the swamp. They were at the point

of perishing when a group of beautiful Indian maidens mysteriously appeared

and shared food with them and helped them find their way home. Subsequent groups

of Indians tried to find the hidden paradise but never could locate it. Bartram

guessed that the swamp might have hidden a remnant population of Yamasees, who

sought asylum from the fury of their enemies, the Creeks.

What Bartram believed true of the Yamasees came true of other displaced Indian

tribes, such as the Creeks and Seminoles, who used the swamps as a reliable

hiding place when Europeans settled the Georgia coast. It is believed that the

great Seminole Indian Osceola spent time in the Okefenokee. In the 1820s, Chief

Billy Bowlegs led his Indians against white homesteaders near and in the swamps.

In 1838, General Charles Floyd, son of the famous Indian fighter John Floyd,

searched the swamp for Billy Bowlegs but never found him. Billy led his Indians

to the Everglades, where he and his men became part of the Seminole tribe. Two

of the largest islands in the swamp are named for Billy and his pursuer.

In

the 1850s, when it was obvious Indians had abandoned the swamp, homesteaders

moved in to claim their piece of it. These isolated and independent families,

such as the Chessers on Chesser Island and the Lees on Billys Island, raised

families and livestock, grew crops, and established a unique culture all their

own. The Chessers' homestead is preserved and open to tour at Suwannee Canal

Recreation Area, and remnants of the Lees' homestead are found on Billys Island,

accessed at Stephen C. Foster State Park.

In

the 1850s, when it was obvious Indians had abandoned the swamp, homesteaders

moved in to claim their piece of it. These isolated and independent families,

such as the Chessers on Chesser Island and the Lees on Billys Island, raised

families and livestock, grew crops, and established a unique culture all their

own. The Chessers' homestead is preserved and open to tour at Suwannee Canal

Recreation Area, and remnants of the Lees' homestead are found on Billys Island,

accessed at Stephen C. Foster State Park.

The swamp has suffered two major insults to its ecosystem, the first in the

1890s. Captain Henry Jackson and a group of investors purchased (912) 238,120

acres of the swamp for $63,101.80, and began a venture to build a canal that

would drain the swamp into the St. Marys River, which would allow for easy access

to cypress trees and rice, cotton, and sugar cane farms. This became known as

"Jackson's Folly." Convict labor, large steam shovels, and gold miners

from North Georgia started digging a trench from the swamp toward Trail Ridge

and westward toward the swamp's prairies. Fortunately, the drainage effort failed

after three years. In 1894, a sawmill was built at Camp Cornelia, and some of

the country's first uses of industrial forestry were attempted, using steam-powered

skidders and logging pullboats. The sawmill produced over 7 million board feet

of lumber. The company hoped to make enough profits on the lumber to continue

the drainage project. Fortunately, there was a glut of lumber and it was unable

to operate profitably. Jackson died of appendicitis in 1895, and his father

took over. The company went into receivership in 1(912) 897 and was sold to

lumberman Charles Hebard of Philadelphia in 1901. Today, the canal serves as

the principal waterway into the heart of the swamp.

The second major insult occurred from 1909 to 1927, when the Hebard Cypress

Company did its best to cut out the swamp's cypress and pine forests. Roughly

2,000 people eventually were at work in the swamp in lumbering or turpentining

activities. The company built a network of elevated trams across the swamp to

get to the magnificent cypresses, some over 1,000 years old. They headquartered

on Billys Island, which became a company boom town that supported 600 residents,

two motels, a movie theater, a grocery store, a school, churches and a "juke

joint." Although the company was unable to clear-cut the swamp, it was

able to remove 425 million board feet of timber, said to be enough to build

42,000 homes. Tens of thousands of railroad crossties were cut. The depletion

of the resource and onset of the Depression slowed the logging efforts, and

the Hebards sold the property to the Federal government, which ended this era.

During the Depression, the Federal government examined a proposal to build a

canal across the swamp that would connect the Atlantic with the Gulf. This alarmed

a naturalist who loved the swamp and its swamper community. Francis Harper was

introduced to the swamp in 1912 when he was 25 years old and a junior member

of a Cornell University biological team. His fascination with the swamp grew,

and he returned many times to continue his explorations of its flora and fauna

and swampers. In 1935, he built a cabin on Chesser Island.

With

the canal project threatening to destroy the swamp, Harper moved to convince

President Franklin D. Roosevelt to make the swamp a national wildlife refuge.

Lucky for the swamp, Harper's wife, Jean, had worked as a tutor to Roosevelt's

children. The Harpers' personal relationship with Roosevelt helped their appeal

get heard, and in 1937, the Federal government purchased the Okefenokee and

made it a national wildlife refuge. In 1974, most of the refuge received protection

as a national wilderness area. Ironically, this forced Harper's beloved swampers

off their property forever. Harper had collected their folklore for years with

the intention of publishing a book, but died at the age of 84 before finishing

his work. A book based on Harper's notes was published posthumously called Okefinokee

Album, by Delma E. Presley.

With

the canal project threatening to destroy the swamp, Harper moved to convince

President Franklin D. Roosevelt to make the swamp a national wildlife refuge.

Lucky for the swamp, Harper's wife, Jean, had worked as a tutor to Roosevelt's

children. The Harpers' personal relationship with Roosevelt helped their appeal

get heard, and in 1937, the Federal government purchased the Okefenokee and

made it a national wildlife refuge. In 1974, most of the refuge received protection

as a national wilderness area. Ironically, this forced Harper's beloved swampers

off their property forever. Harper had collected their folklore for years with

the intention of publishing a book, but died at the age of 84 before finishing

his work. A book based on Harper's notes was published posthumously called Okefinokee

Album, by Delma E. Presley.

In the early 1950s, several droughts dried the swamp to combustible conditions.

In 1954 and 1955, terrible fires swept through the swamp and surrounding uplands,

burning more than half a million acres. This caused alarm among many conservation

and forestry groups, who asked Congress to build a dam near the western side

of the swamp to keep it in wet conditions. The sill, which was built in 1957,

keeps the swamp unnaturally wet in the area of the river and has resulted in

further debate about the management of the swamp and the effect of fires on

its natural system.

The latest threat to the swamp occurred in the late 1990s, when the DuPont Corporation

purchased the mineral rights to Trail Ridge with the intention of strip-mining

the ancient dune for valuable titanium deposits. Scientists believe such a drastic

alteration of the landscape that backs up the waters of the swamp may destroy

it forever. Opposition to the plan is fierce but the issue remains unresolved

as this book goes to press.

Read

and add comments about this page

Reader-Contributed Links to the Georgia Coast and Okefenokee Book:

Visiting

the swamp can be somewhat confusing. There is no one park you go to that offers

the entirety of the Okefenokee experience. Visitors have four choices of parks,

each with their own set of natural qualities and recreation opportunities. Three

parks are located on the eastern side of the swamp, and one park is located

on the southwestern side. Because of the size of the swamp, visiting the full

complement of parks requires some driving because one must travel around the

perimeter of the wetland, which is larger than the interior of Interstate 285

or all the barrier islands of Georgia combined. The most popular activities

in the swamp are sightseeing, boating, and fishing.

Visiting

the swamp can be somewhat confusing. There is no one park you go to that offers

the entirety of the Okefenokee experience. Visitors have four choices of parks,

each with their own set of natural qualities and recreation opportunities. Three

parks are located on the eastern side of the swamp, and one park is located

on the southwestern side. Because of the size of the swamp, visiting the full

complement of parks requires some driving because one must travel around the

perimeter of the wetland, which is larger than the interior of Interstate 285

or all the barrier islands of Georgia combined. The most popular activities

in the swamp are sightseeing, boating, and fishing.

The

Okefenokee Swamp's Natural Features

The

Okefenokee Swamp's Natural Features  Geologically,

the swamp is a newborn, with the oldest peat estimated to be 8,000 years old.

Approximately 200,000 years ago, the Atlantic Ocean covered the swamp. As the

climate cooled during subsequent ice ages, sea level dropped, and as the seas

receded, high dunes formed at various shorelines. Around 140,000 years ago,

a giant dune line known as Trail Ridge was formed, stretching from Starke, Florida

to Jesup, Georgia. This ridge, which makes up the eastern edge of the swamp,

acted as a dam to southeastern flowing rivers, causing water to pool behind

the ridge or flow around it to gaps in the ridge. The Satilla River flows through

one such gap, while the St. Marys River is forced south before reaching a gap,

where it moves east then north and east to the Atlantic Ocean.

Geologically,

the swamp is a newborn, with the oldest peat estimated to be 8,000 years old.

Approximately 200,000 years ago, the Atlantic Ocean covered the swamp. As the

climate cooled during subsequent ice ages, sea level dropped, and as the seas

receded, high dunes formed at various shorelines. Around 140,000 years ago,

a giant dune line known as Trail Ridge was formed, stretching from Starke, Florida

to Jesup, Georgia. This ridge, which makes up the eastern edge of the swamp,

acted as a dam to southeastern flowing rivers, causing water to pool behind

the ridge or flow around it to gaps in the ridge. The Satilla River flows through

one such gap, while the St. Marys River is forced south before reaching a gap,

where it moves east then north and east to the Atlantic Ocean.

Today,

the swamp has roughtly 70 tree islands that make up 10 percent of the swamp.

The signature cypress forest occupies around 25 percent. Approximately 20 percent

of the swamp is prairie, consisting of grasses and sedges, moss, ferns, and

rushes. Emergent plants such as golden club, pickerelweed, and yellow-eyed grass

are characteristic plants of the prairie. Blue flag irises add splashes of lavender.

And roughly 33 percent of the swamp is scrub-shrub, with evergreen, leathery

leafed shrubs such as dahoon holly and fetterbush dominating the landscape.

The rest of the swamp is mixed pine uplands.

Today,

the swamp has roughtly 70 tree islands that make up 10 percent of the swamp.

The signature cypress forest occupies around 25 percent. Approximately 20 percent

of the swamp is prairie, consisting of grasses and sedges, moss, ferns, and

rushes. Emergent plants such as golden club, pickerelweed, and yellow-eyed grass

are characteristic plants of the prairie. Blue flag irises add splashes of lavender.

And roughly 33 percent of the swamp is scrub-shrub, with evergreen, leathery

leafed shrubs such as dahoon holly and fetterbush dominating the landscape.

The rest of the swamp is mixed pine uplands.

The

Okefenokee Swamp's Human History

The

Okefenokee Swamp's Human History  In

the 1850s, when it was obvious Indians had abandoned the swamp, homesteaders

moved in to claim their piece of it. These isolated and independent families,

such as the Chessers on Chesser Island and the Lees on Billys Island, raised

families and livestock, grew crops, and established a unique culture all their

own. The Chessers' homestead is preserved and open to tour at Suwannee Canal

Recreation Area, and remnants of the Lees' homestead are found on Billys Island,

accessed at Stephen C. Foster State Park.

In

the 1850s, when it was obvious Indians had abandoned the swamp, homesteaders

moved in to claim their piece of it. These isolated and independent families,

such as the Chessers on Chesser Island and the Lees on Billys Island, raised

families and livestock, grew crops, and established a unique culture all their

own. The Chessers' homestead is preserved and open to tour at Suwannee Canal

Recreation Area, and remnants of the Lees' homestead are found on Billys Island,

accessed at Stephen C. Foster State Park.

With

the canal project threatening to destroy the swamp, Harper moved to convince

President Franklin D. Roosevelt to make the swamp a national wildlife refuge.

Lucky for the swamp, Harper's wife, Jean, had worked as a tutor to Roosevelt's

children. The Harpers' personal relationship with Roosevelt helped their appeal

get heard, and in 1937, the Federal government purchased the Okefenokee and

made it a national wildlife refuge. In 1974, most of the refuge received protection

as a national wilderness area. Ironically, this forced Harper's beloved swampers

off their property forever. Harper had collected their folklore for years with

the intention of publishing a book, but died at the age of 84 before finishing

his work. A book based on Harper's notes was published posthumously called Okefinokee

Album, by Delma E. Presley.

With

the canal project threatening to destroy the swamp, Harper moved to convince

President Franklin D. Roosevelt to make the swamp a national wildlife refuge.

Lucky for the swamp, Harper's wife, Jean, had worked as a tutor to Roosevelt's

children. The Harpers' personal relationship with Roosevelt helped their appeal

get heard, and in 1937, the Federal government purchased the Okefenokee and

made it a national wildlife refuge. In 1974, most of the refuge received protection

as a national wilderness area. Ironically, this forced Harper's beloved swampers

off their property forever. Harper had collected their folklore for years with

the intention of publishing a book, but died at the age of 84 before finishing

his work. A book based on Harper's notes was published posthumously called Okefinokee

Album, by Delma E. Presley.