The Natural Georgia Series: The Okefenokee Swamp

|

The Natural Georgia Series: The Okefenokee Swamp |

|

When asked about its future, scientists speak of two issues facing the Okefenokee

National Wildlife Refuge. Throughout its history, the swamp has continued to

exist despite attempts to drain, log, and develop. As they struggle to understand

the Okefenokee, scientists ask how much they can manipulate the swamp without

changing its nature.

On the west side, a debate rages over the Suwannee River Sill. Because of a

history of wildfires which frightened people who owned property and lived around

the Okefenokee, this earthen dam was built to hold water in the swamp and prevent

it from burning. Now that the structure is in need of repair, people are wondering

if manipulating the natural cycle of fire in the swamp was such a good idea

in the first place. Examining the sill includes talk of removing it, which could

have drastic impacts on public use.

On the east side, E.I. DuPont De Nemours & Company's proposal to mine

titanium minerals along Trail Ridge is the most significant issue ever to face

the Okefenokee. While DuPont maintains it can conduct it's operation in an environmentally

friendly way, some wonder if it will destroy the Okefenokee. The jury is still

out, but preliminary data suggests that altering Trail Ridge may mean changing

the Okefenokee forever.

More than 400,000 people visit the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge each

year, and the economic impact of these tourists in Charlton, Ware, and Clinch

counties is greater than $55 million. Interest in the area only seems to be

increasing, and management plans suggest that the refuge could sustain up to

800,000 visitors each year. The national wildlife refuge and the tourist industry

also provide jobs for citizens living around the Okefenokee.

Besides its economic value, the Okefenokee provides valuable habitat for plants

and animals, some of them threatened or endangered species and others candidates

for protected status. The swamp's influence on cultural history in the southeast

is undeniable. Many residents of Charlton, Clinch, and Ware counties trace their

roots to family that lived or worked in the Okefenokee, and view the swamp as

an important part of their heritage. The swamp is the headwaters for the Suwannee

and the St. Mary's rivers, which depend on its health for their own.

Research will continue to fuel the debate over the Suwannee River Sill and

DuPont's mining proposal. Learning more is crucial to the survival not only

of the Okefenokee, but also the living things which depend on the rich swamp

ecosystem. Because of the interconnectedness of the swamp, both issues have

the potential to impact plants, animals, property and people in and around the

entire Okefenokee.

Fire is a necessary part of the swamp ecosystem. When it burns the swamp,

usual plant succession is interrupted, preventing swamp prairies from filling

with cypresses, black gums, and bays and becoming woodland. As a secondary benefit,

fire releases nutrients such as phosphorous and potassium built up in vegetative

matter, making them available to help the swamp grow. When fire burns fierce

enough to do its job in the Okefenokee, it can be a frightening force.

The first documented fire is the "Big Fire" of 1844. No white men

had settled the swamp, but people living on the outskirts later recalled smoke

hanging over the countryside for several weeks, sometimes in a cloud so thick

it hid the sun.

In 1932, a year when the swamp was unusually dry, a fire burned many of the

swamp's bay trees, about 40 to 50 million board feet of its black gums, and

several million feet of slash pines. It threw fiery bits of moss onto the streets

of town a few miles away.

People today still remember the fires of 1954 and 1955. During these two years,

five major fires burnt almost 360,000 acres of the Okefenokee (almost four fifths

of the total area) and 142,000 additional acres of the neighboring uplands.

The fires were preceded by a terrible drought - in 1954 only 26 inches of rain,

less than half the annual average, fell in the swamp. Water levels were so low

that Minnie's Lake and Big Water were almost dry, and because of a lack of surface

water, boat travel became nearly impossible.

When the series of fires burned, much of southeast Georgia lay under such

a heavy blanket of smoke that drivers were forced to travel with their headlights

on high beam at midday. Heavy rains finally drenched the fires in the summer

of 1955, but by this time, many areas of the Okefenokee were reported to be

unrecognizable.

"That fire scared a lot of people in this portion of the world,"

says Jim Burkhart, Refuge Ranger for the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge.

It scared Congress, too, which decided that drastic fire demanded action. At

the urging of conservationists, forestry officials, and owners of land around

the swamp, Congress mandated the construction of the Suwannee River Sill, a

five-mile-long earthen dam built in 1962. With two concrete and steel water

control structures which provide an outlet for the Suwannee River, the sill

was built to hold water in the swamp and prevent catastrophic fire.

Today, flaws in the construction of the sill have led to damage which requires

costly repair. Naturally occurring acid in the swamp water is eating holes the

size of basketballs in the concrete. Leakage from these holes creates a strong

current which the refuge says is dangerous to boaters and anglers. Refuge reports

also say that further deterioration could cause a breach in the sill and possible

devastating consequences downstream.

Instead of asking whether or not the sill should be repaired, some are asking

whether or not it should be removed. Some want to see the headwaters of the

Suwannee River restored to its natural state, while others argue that preventing

fire completely was a bad idea from the start. The majority of the land around

the swamp is held by private or commercial timber operators who have an economic

interest in preventing fire which could leave the swamp and reach their land,

but preliminary findings of a study on the sill suggest it may never have been

capable of preventing fire in the entire Okefenokee.

"What is receiving the most impact is the river floodplain, which probably

naturally burns less often," says Cynthia Loftin, a University of Florida

graduate research assistant-Ph.D. candidate who has conducted the most recent

research on the sill. "The rest of the swamp, from our preliminary analysis,

is not being affected. The sill is not tall enough and long enough, and there

is not enough water coming in to impound to flood the whole place."

Loftin says the sill's effects seem to be localized to approximately 10,000

meters from the impoundment, reaching out in a semicircle. According to refuge

reports, the sill's greatest effects seem to be not during drought but during

high water. During drought the zone of influence decreases to only about one

percent of the swamp.

If the area around the sill was left untouched, it would be a wet pine forest

which would naturally flood and dry out periodically. Because of these periodic

floods, peat would not build up in the floodplain and the area would probably

be naturally less susceptible to fire than other areas of the swamp.

Instead the area around the sill remains under approximately two meters of

water most of the year. It is, in effect, an impounded lake where peat and vegetation

builds. By allowing this build-up to occur, the impoundment could be increasing

the chance of fire in a naturally fire-resistant floodplain.

In the 1990s the swamp has proven it can and still will burn in areas where

peat has accumulated. A fire in 1990 in the southwest corner of the swamp burned

23,000 acres and cost $7-9 million to fight for eight weeks. The only thing

that put it out was a tropical depression which dropped four to five inches

of rain on the swamp. In 1993, another fire near the Georgia-Florida line burned

5,000 acres.

By holding water in the area and keeping trees and shrubs constantly submerged,

the sill may also be causing damage to vegetation and in turn the wildlife which

uses it, including the establishment of osprey nests and a rookery for ibis,

herons, and egrets. Because fish can pass over the sill spillway but cannot

return to spawn, the structure has changed the fishery within the Suwannee River

and the swamp.

Regardless of how well the sill is or is not working, refuge managers' attitudes

toward fire have changed since the 1960s. When the sill was built, the country

was controlled by what is called the "Smoky Bear mentality" - the

belief that all fire is destructive and bad. Today, the refuge recognizes fire's

important role in the Okefenokee and prepares for it instead of trying to prevent

it.

Fred Wetzell, Supervisory Forester and Fire Management Officer for the Okefenokee

National Wildlife Refuge, receives help from the private and commercial landowners

around the Okefenokee who are willing to invest time and money to protect their

timber. In 1994, a group of such landowners, brought together by a concern for

the danger and expense of fighting wildfires which leave the swamp, formed an

organization called GOAL (Greater Okefenokee Association of Landowners.) Currently

more than 80 people who are landowners or represent landowners are on the GOAL

mailing list. These landowners and land managers represent more than 2 million

acres in south Georgia and north Florida.

Wetzell works with GOAL to maintain the swamp edge break, a 200-mile dirt

road around the perimeter of the Okefenokee which can act as a buffer zone to

keep fire from entering or leaving the swamp, and make it easier to escape and

fight fire in the area. But what many consider to be GOAL's greatest contribution

to fire management efforts are the helicopter dip sites the organization has

paid for and built around the Okefenokee. These are water holes where helicopters

with buckets can dip in and retrieve water to use fighting fires. Wetzell says

there is now a dip site approximately every three miles around the swamp, and

most of these sites are on private property. "GOAL is so unique in the

fire community it's almost unbelievable," Wetzell says.

It takes a fierce fire to interrupt the successional process - one even stronger

than the fires of 1954 and 1955. Although these fires spread far and wide, there

is no data to suggest they burned into the swamp's peat bed and created new

prairies. According Wetzell, when a fire occurs today, when water levels are

at or above normal, it "top kills," sweeping through the swamp very

hot and very fast. "It burns everything off to the ground, and that just

stimulates sprouting from the root," Wetzell says. "So you get a more

tangled mess than you had to begin with.

"It's only the creation of open water that prolongs the swamp. There

is only about two percent of open water in the swamp now," Wetzell says.

It is impossible to know how much of the Okefenokee was open area when it was

created, but Wetzell feels it was a great deal more than there is now.

In order for a fire to do more than top kill, the peat, which is several feet

deep in some places, must be dry. So dry that Wetzell says, "I would like

to be in Alaska if it was dry enough to burn down to the sand. I don't want

to be here." Droughts severe enough to lead to major fires occur in the

Okefenokee roughly every 30 to 50 years, he says.

Wetzell believes the refuge cannot judge how well the sill prevents fires

because since the sill has been in place, climate conditions have not been right

for a large-scale fire in the Okefenokee. "We don't know for sure how well

the sill will work when we have climatic drought. We haven't faced it,"

Wetzell says. "When we go through a dry winter, and then a dry spring and

summer, then we'll see what happens."

Although Wetzell and his men conduct controlled burns in the uplands to clean

out grass, leaves, and limbs which would act as fuel for a spreading fire and

to restore habitat, they do not start fires in the swamp which could grow large

enough to create open water areas. "I haven't got the guts to just go out

there and set a fire in the swamp. Nobody does when we think it would do what

it needs to do," Wetzell says. And, he says, he cannot be liable and the

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) cannot be liable for the damage such

a fire could cause on property outside the refuge.

Lightning is the most infamous arsonist in the Okefenokee. Most swamp blazes

begin with a bolt striking a tree in the uplands, spread from the pinelands

to the fringes of the swamp, and probe into the interior, finally reaching the

peat. According to Wetzell, on almost any given summer afternoon when there

is an electrical storm in the Okefenokee, he can point to over 500 lightning

strikes. "If we had a very droughty condition, it would only take one afternoon,"

Wetzell says. "It will happen."

Believing droughts and fire are inevitable, Wetzell has his doubts about whether

or not the sill will help the swamp. The Okefenokee covers such a large area,

roughly 400,000 acres, and the sill only affects a small portion on the western

side. "Only part of the swamp drains through the Suwannee River basin,"

Wetzell says. "The part that drains out the St. Marys is not affected at

all by the sill - at least that's what it looks like."

That's what it looks like, but no one knows for sure. As a result, each year

since fiscal year 1995, the refuge has submitted a budget proposal to conduct

an environmental impact study on the sill's impacts on wildlife, recreation,

and economic interests. This study would consider several alternatives with

respect to the fate of the sill, including repairing the damage to the current

structure, doing nothing, and removing the sill completely. Conducting an environmental

impact study would cost approximately $1 million, including consulting, USFWS

employee oversight, and engineering designs. Depending on the repair option

chosen as a result of an environmental impact study, proposals for repair or

replacement of the sill run from $3.3 to $6.3 million. To date, the proposal

has not been funded.

Wetzell says, "We maintain the sill as Congress tells us to, but we would

like today's research to look at it and tell us whether it's worth anything

or not. We have our doubts."

Until an environmental impact study is completed, it is also impossible to

know the effects of removing the sill. Loftin says removing the sill might make

the area a more productive river floodplain with better fish resources, and

open the floodplain to new educational uses like interpretive walks. She does

not deny that removing the sill would have drastic effects on public use of

the Okefenokee. The area around the sill is currently one of the most popular

fishing spots in the swamp. Removing the sill could be bad for anglers. And

even visitors who don't like to fish, who just enjoy the Okefenokee experience,

could be affected. Removing the sill could make water levels and boat travel

more seasonal and limit access to areas of the swamp during certain times of

the year.

If it comes time to decide whether or not the sill should be removed, Jim

Burkhart believes conservation groups will be on one side and timber operators

and tourists will be on the other. Conservation groups, Burkhart says, which

will want to see the Suwannee River untamed and returned to its natural state

as long as it is determined that that won't cause problems in other places.

But he believes commercial timber companies who own land around the swamp and

the visiting public will fight to see the sill stay put. Burkhart says timber

companies see the sill as fire protection, and visitors who are used to normal

water levels, won't want to have a short window of opportunity to enjoy the

whole swamp.

One of the United States' most desirable tracts of titanium-bearing ore rests

in Trail Ridge alongside the Okefenokee. E.I. DuPont De Nemours & Company

owns the mineral rights on the land and plans to mine it, but scientists and

environmentalists are concerned mining could harm the swamp. The company currently

owns or leases 38,000 acres along Trail Ridge and wants to develop a titanium

sand mine on half of the land, or approximately 20,000 acres. During the proposed

50-year operation, zircon, staurolite, and the titanium minerals ilmenite, rutile,

and leucoxene would be removed.

Titanium is a light-weight, silver-gray metal used to construct items which

require strength without weight - items such as aircraft parts and industrial

ceramics. Combining titanium with oxygen produces titanium dioxide, a white

pigment used in toothpaste, plastic picnic forks, creamy Oreo filling, the slick

pages of this magazine, and even the M on M&Ms. It is a $7 billion global

industry.

DuPont is the world's leading supplier of titanium, accounting for one quarter

of the total global supply, and is one of only two companies that mine titanium

ore in the United States. In addition to mining, Delaware-based DuPont produces

the white pigment at four U.S. plants.

Almost 200 years old, DuPont is the world's largest chemical corporation,

last year reporting $42 billion in revenue. The company, which produces products

ranging from lycra to the nylon in backpacks, has also been one of the leading

pollutors of the 20th century. From the mid-1970s through the early 1990s DuPont

continued to manufacture chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) despite warnings of harm

to the ozone layer. In the 1994 EPA Toxic Release Inventory, four of the top

20 biggest pollutors to air, ground, and water were DuPont facilities. And from

1990-1994, DuPont had 70 major chemical spills (the industry average was 27),

more than any other major chemical company.

Particularly in the last five years, DuPont has worked hard to clean up its

environmental image. In 1994 it formed the DuPont Land Legacy Program which

is designed to place surplus company properties into protected status. When

DuPont built a fiber plant in Asturias, Spain in 1990, it also launched a heritage

project committed to preserving cultural and natural history and promoting biodiversity.

And back in the United States, the company has received environmental awards

for reducing wastes and emissions.

Because of stringent environmental regulations in this country, most companies

look to do their titanium mining abroad. Proud to be a U.S.-based company, Paul

Tebo, vice president, DuPont Safety, Health, and Environment, says DuPont is

dedicated to searching for and finding titanium deposits to mine in this country.

"The tract of land next to the Okefenokee is the only place in the United

States where the ore is perfect for what we do," says Tebo.

DuPont will only say it has invested "millions of dollars" in the

site and believes is can conduct the mining in a manner which will not harm

the Okefenokee. Because the titanium business is a highly competitive, global

business, DuPont is not willing to divulge the exact amount of mineral involved

or how much money the company stands to make from the mining.

Trail Ridge, which forms the eastern boundary of the Okefenokee, was formed

almost 250,000 years ago, when the shoreline of the Atlantic Ocean lay approximately

70 miles inland from the present Georgia coast. Ocean currents and surf action

built a narrow sandbar, about 40 miles long, and a shallow lagoon formed behind

it to the west. The waters and sediments which crashed against this sandbar

left behind a rich deposit of minerals, including titanium-bearing ore.

When the ocean retreated, the sandbar survived as Trail Ridge. The lagoon

behind it drained, and the sand basin later became the bed of the Okefenokee.

Today Trail Ridge, which stretches from Gainesville, Florida to Jesup, Georgia,

is one to two miles wide and acts as a natural dam for the Okefenokee. If the

swamp is water in a bowl, Trail Ridge acts as one side of that bowl. The ridge

does break away from the Okefenokee, to the north and to the south. Further

north, where there is a break in Trail Ridge, the Satilla River flows toward

the Atlantic. To the south, the St. Marys River breaks through the ridge on

its course toward the sea.

DuPont's land is really two tracts of land, both immediately adjacent to the

Okefenokee. One is on the north side of the entrance road into the Suwannee

Canal Recreation Area and was purchased from Union Camp late in 1991. The other

tract, south of the same entrance road, DuPont began leasing the mineral rights

on from Toledo Manufacturing in 1996. Both Union Camp and Toledo continue to

use the land for commercial timber operations.

If the mining takes place, it may not be tucked away far from areas where

people visit and enjoy the Okefenokee. DuPont could dredge alongside or right

across the entrance road used by thousands of refuge visitors each year, Suwannee

Canal Road. The USFWS headquarters building is also on this road, just outside

the boundary of the National Wildlife Refuge. According to Skippy Reeves, Okefenokee

National Wildlife Refuge Manager, building on refuge land would have required

an appropriation from Congress - "which would have taken forever."

So it was built on property which DuPont owns and leases back to the building

developer.

The mining process DuPont proposes to use alongside the Okefenokee, in Charlton

County, is similar to its current mining operation in Starke, Florida, which

it has operated for about 40 years. To begin the process, DuPont clears all

vegetation in a one-square-mile area, and strips and stores one foot of topsoil

to be used later in reclamation. Then, a 20-acre pond, 45 to 50 feet deep, is

dredged and allowed to fill naturally with groundwater. Floating behind the

dredge is a wet mill which uses gravity separation techniques to remove the

valuable minerals. These minerals only make up about two percent of the sand

volume. Once they are removed, the other 98 percent is backfilled into the pit

behind the dredge.

DuPont plans to continue operating its dry mill in Starke, so minerals extracted

in Charlton County will be trucked there - an estimated 350 to 400 truckloads

per week. Once the dredge has left an area, the topsoil will be replaced and

the land will be contoured to approximate pre-mine elevations and drainage patterns.

DuPont plans to "recreate" wetlands and revegetate the mined area

with grasses and pine trees. At any one time, three square miles are affected

by the mining operation: in the middle is one square mile being mined, in front

is one square mile being clear-cut and prepared for mining, and behind is one

square mile being "reclaimed."

DuPont proposes to run this mining operation seven days a week, 24 hours a

day, for 50 years. The company says it will employ 60 people at its mining operation

in Charlton County, but it plans to close its Starke facility at approximately

the same time work begins in Georgia, leaving Florida employees to look for

work nearby. To proceed with the mining, DuPont must first receive a series

of state permits and eventually a U.S. Army Corps of Engineer's Section 404

permit.

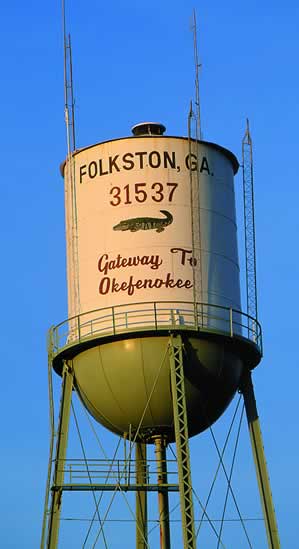

There are people in Folkston who welcome the mining as a boost to the local

economy, but leaders on the state and national level have voiced serious concern

about the proposed mining operation and how it might harm the swamp. In early

April 1997, after visiting the Okefenokee and flying over DuPont's Starke facility,

Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt said he believed the swamp would suffer as

a result of the mining and announced plans to send a letter to DuPont's board

of directors asking them to withdraw their mining plans.

Georgia's Board of Natural Resources, which sets policy for the state Department

of Natural Resources and the Environmental Protection Division (EPD), has also

come out in opposition to the mining. The board cannot issue permits, EPD Director

Harold Reheis is the only authority by law that can do that, but Board Chairman

Joe Beverly said he wanted the board to express its concern up front. Without

state permits, DuPont cannot be granted the federal permit it needs.

As a result of this outcry, DuPont has announced it will stop its mining plans

and operations and enter into an intensified and expanded collaborative process

with key environmental groups, government bodies, and local citizens. DuPont

says this collaborative will consider all possible uses of the land including

"mining, not mining, and everything in between."

DuPont says it will not drive the collaborative, but rather plans to enlist

an independent third party to facilitate the decision-making process and will

live with whatever decision this collaborative reaches. DuPont says it cannot

simply abandon the project without further research because of the amount and

quality of the mineral at stake.

Trail Ridge consists of highly stratified soil, with individual layers that

have been compared to layers in a parfait. Among the layers of sand, are tiny

clay layers, called hardpan, which are believed to channel water seeping down

into the ridge into the Okefenokee. Scientists are worried the dredging process

will stir up and forever change the soil layers.

Sidney Bacchus, who is conducting doctoral research in ecology at the University

of Georgia, was recognized with the 1997 John "Alec" Little Water

Resources Scholarship Award for her significant contributions to water resources

research. She says when surface water seeps into sandy Trail Ridge and hits

this hardpan, it slows down, and instead of flowing straight down to the Floridian

Aquifer, it flows laterally into the wetlands of the Okefenokee Swamp.

Bacchus says, "DuPont will be able to regain the approximate contours

of what was there before, but they will have homogenized the clay layers, they

won't exist any more. We don't know how long it will take to reform the clay."

Discussing concerns about destroying soil stratification just involves looking

at mining the uplands on Trail Ridge. Looking at mining the pockets of wetlands

along Trail Ridge raises even more and different concerns. DuPont's mining plans

involve digging large holes which will fill with enough groundwater to float

their wet mill - "equipment the size of a large hotel," Bacchus says.

The sides of these pits do not have solid walls. To fill the space in DuPont's

pit, groundwater rushes from off-site areas, including the Okefenokee, lowering

the water table there. The water table is a very important and delicate issue,

Bacchus says, because slight changes can have big effects. "Plants' roots

are very shallow in the Okefenokee, and if the water table drops even a foot,

it could have a drastic effect," she says. "In granting DuPont its

permits, the Army Corps of Engineers will want to know how many acres they are

mining. There may be very few that will be dug up and spit out. But the real

issue is how many wetlands will be destroyed off-site."

DuPont's plans to pump groundwater from the Floridan Aquifer at a rate of

approximately 250 gallons per minute could also affect hydrology. The water

will be used to clean the equipment and facility and for employee restrooms

at the mining site. No one is exactly sure how much, but some groundwater flows

in and out of the swamp, affecting water levels there.

As Cynthia Loftin conducts her study of the sill on the west side of the swamp,

she is not collecting information on groundwater's effect on swamp hydrology

because the exchange is not significant there. Previous studies showed that

only two to three percent of the water in the Okefenokee came from groundflow

- at least on the west side. "In other parts of the swamp, groundwater

may be important," she says. "There may be some groundwater coming

up and groundwater going out, supplementing what is in the swamp."

Bacchus says water chemistry data shows water is already being drawn from

the swamp because of large withdrawals from the Floridan Aquifer. "When

there are large industrial withdrawals, even as far away as Brunswick, that

pulls water from areas like these depressional wetlands," Bacchus says.

"If DuPont's wells are dug, they will pull water from the Floridan Aquifer,

and that can have impacts way beyond the Okefenokee."

Jon Samborski, DuPont Engineering Associate, says the company has demonstrated

its ability to return land contours and drainage to approximately pre-mining

conditions and restore uplands to normal timber operations at its site in Florida.

He admits the mining process mixes hardpan with sand, but says that "does

not significantly alter the hydrological characteristics of Trail Ridge itself."

DuPont says the vegetation and wildlife inventories taken after reclamation

are proof of the company's successful work. The staff of the Georgia Department

of Natural Resources (DNR) is not entirely convinced.

Tip Hon, DNR Regional Wildlife Supervisor, says DuPont's reclamation work

will be great for growing pine trees, but terrible for wildlife. "From

what we've seen of Starke, the understory vegetation is gone, and that's a short-rotation

pine plantation operator's dream come true. They won't have to use herbicides

to keep the understory from sucking nutrients out of the soil," Hon says.

"When they churn and mix the soil into a parfait, the nutrients all move

to the top layer of the soil. That's better for pine plantations, too."

Hon says the habitat found after reclamation is much less diverse than the original,

and the wildlife found on site suffers because of that.

He uses the black bear as an example of one large game species which could

suffer as a result of the mining. There is a six-day hunting season for bears

in Charlton County, and the state estimates that 49 percent of the bears taken

in Georgia are killed there. Within Charlton County, it is estimated that 95

percent of the bears are killed on Trail Ridge. Looking at those figures, Hon

estimates 40 percent of the bears harvested in Georgia are harvested on Trail

Ridge.

What attracts bears to Trail Ridge is the diversity and maturity of its habitats,

which will be destroyed as DuPont takes over Trail Ridge mile by mile. "DuPont

is not going to be able to reproduce 60-, 80-, 100-year-old blackgum swamp,"

Hon says. "They can recreate wetlands with cattails and willows, but not

a forested wetland."

Bears will have a better chance of survival than some animals, though. They

have been known to move 15 miles in response to a food source and have several-thousand-acre

home ranges. They also can live throughout the swamp and are not solely dependent

on the habitat along Trail Ridge.

The gopher tortoise, on the other hand, expends its lifetime in less than

one acre. It lives in the sandy soil of Trail Ridge where the water table is

at least three feet below the surface. When DuPont scrapes off a foot of topsoil,

Hon says the tunnels of gopher tortoises will collapse, trapping the animals

inside. "There's a good chance slow-moving, sedentary animals will be ground

up in the machinery," Hon says. "If there's any titanium in their

bodies, I guess DuPont will get that."

An alternative to sucking creatures into the mill would be to catch animals

like the gopher tortoise and move them, but move them where, Hon asks. "The

flatwoods of the Okefenokee are not potential habitat, and neither are the pine

plantations on the other side," he says. "Trail Ridge is their island

in a sea of wetlands and pine plantations. Their habitat is not a real common

commodity."

Red-cockaded woodpeckers would also have trouble finding a new home. Hon says

the DNR believes there are five to seven colonies of the birds living on DuPont's

38,000 acres. Displacing them leaves the birds looking for another stand of

mature longleaf and slash pine - another stand that is not already occupied

by a colony of red-cockaded woodpeckers. There are also indigo snakes which

depend on fragile gopher tortoise habitat, flatwood salamanders which would

probably be ground up in the mill, the microorganisms that live in the soil,

and the list goes on and on. Hon says the outlook is "dismal" for

wildlife if DuPont proceeds with its mining proposal.

The mining process also has the potential to release mercury and other contaminants

into the swamp, affecting the area's groundwater sources, plants, and animals.

Right now mercury and other suspected contaminants such as iron, herbicides

and pesticides tied to land use, and radioactive materials are locked in the

soils along Trail Ridge. By disturbing the soils with mining, these contaminants

could be released. It is impossible to predict how much of the contaminants

exist and where, but Greg Masson, a USFWS ecologist and environmental contaminants

specialist for the area around the Okefenokee, says it would be best to "let

sleeping dogs lie."

According to Masson the swamp already has mercury levels high enough to be

of concern. No one is sure where the mercury is coming from, but Masson says

scientists have two guesses: (1) the mercury may be the result of aerial deposition,

or (2) elemental mercury which builds up in vegetation may be mobilizing as

a result of the acid conditions of the swamp.

Samborski says DuPont is testing on site in Georgia and is finding no contaminants.

But the company will expand its testing program and continue its testing he

says until the issue is resolved.

The USFWS also has more basic concerns about how mining would affect the Okefenokee

experience. Staff members are concerned that noise and air pollution caused

by DuPont will ruin the wilderness experience for visitors. Samborski says that's

just not the case. He says the mining process is an electric operation and that

there are "no crushers, grinders, or diesel generators running. When you

stand beside the dredge pond, what you hear is the sound of running water. It's

reminiscent of the sound of a waterfall."

It is the roar and exhaust of trucks traveling in and out of the swamp, the

smoke and soot generated as the land is cleared, and the glaring lights of a

24-hour mining operation that the USFWS is concerned about. And there are aesthetic

concerns, including the transformation of scenic lands into raw, open pits.

Whether DuPont expected it or not, it is getting an emotional response to

its proposal. Most organizations and agencies that are speaking out on the proposed

mining issue are speaking out against it or at least voicing serious concerns.

The Georgia Wildlife Federation supports DuPont's efforts to form a collaborative,

but does not favor a mining alternative. "We think the collaborative process

will come around to a no mining alternative," said Jerry McCollum, President

of the Georgia Wildlife Federation. "But no harm can come of further study."

A wildlife biologist who has conducted research in the Okefenokee, McCollum

believes people are responding intuitively to DuPont's proposal, that the science

is not changing and never will change people's minds: "I think when people

hear DuPont say, 'We're going to mine alongside the Okefenokee, but it is not

going to hurt the swamp and scientists can prove it,' it's like people are hearing,

'I'm going to slap your Mama, but I'm not going to hurt her.'"

While the USFWS maintains a working relationship with DuPont, refuge reports

state that "the Service is firm in its belief that no impacts to the Okefenokee

Swamp or the St. Mary's River, resulting from this project, should be allowed."

Skippy Reeves put it this way: "DuPont is putting significant in front

of the word impact. We are determining if the mining will have any impact."

Some members of the environmental community feel that no impact or even no

significant impact as a result of the mining is an impossible goal, and they

believe DuPont knows it. People believe DuPont bought and leased the land so

recently, long after the national wildlife refuge was formed, that the company

could not have believed its mining proposal would be approved.

These environmentalists call what DuPont is doing "greenmail" -

a form of blackmail that involves buying sensitive lands in order to use them

as a bargaining chip to get something else they really want. They compare the

threat the Okefenokee faces to a similar situation at Yellowstone National Park.

A company who proposed to mine for gold on land next to Yellowstone eventually

agreed to give up its land in exchange for federal land somewhere else.

"Our intent was not to get the land and hold it," says Paul Tebo.

Samborski says, "There is absolutely no truth to that. Our interests are

strictly in titanium minerals. The land is not a poker chip. There is no covert

plot." He says the company did survey other portions of Trail Ridge for

titanium and did not target the Okefenokee. "At least at this time, we

do not feel mining could be supported on areas of Trail Ridge other than this

tract." DuPont is quick to remind its critics that the land the company

has purchased or leased is not pristine, that it has already been highly disturbed

by timber operations. The process of growing and harvesting timber does impact

land and lead to problems such as erosion. Each timber company is different

but some also use herbicides and fertilizers - other sources of nonpoint-source

pollution - as part of their operations. While the USFWS does agree timber operations

affect the swamp, John Kasbohn, a USFWS ecologist, says overall it is a compatible

use of the land next to the Okefenokee.

"Mining will cause damage to the subsurface that timber operations never touch," Kasbohn says. "Anything people do to manage their property has some sort of an effect - whether it's timber operations outside or us thinning a stand on an island inside the refuge. We have to ask ourselves, What are the tradeoffs? And we think the tradeoffs are too great with the mining operation."

Read and add comments about this page

Go back to previous page. Go to Okefenokee Swamp contents page. Go to Sherpa Guides home.

[ Previous Topic | Next Topic ]