The Natural Georgia Series: The Flint River

|

The Natural Georgia Series: The Flint River |

|

The

land between the Flint River and the river it historically fed into, the Chattahoochee,

is a region that is tightly intertwined with the history of Georgia and America.

Within these natural boundaries sprang events with national scope. What was

occurring in America was reflected in what was happening in the region, and

events that occurred in the region greatly

The

land between the Flint River and the river it historically fed into, the Chattahoochee,

is a region that is tightly intertwined with the history of Georgia and America.

Within these natural boundaries sprang events with national scope. What was

occurring in America was reflected in what was happening in the region, and

events that occurred in the region greatly

affected the policies of an emerging nation.

Some of the first European explorers to come to America made their way up the Flint River and found a society of people who had been inhabiting this land for thousands of years-cutting paths through the forests, canoeing the waters, and planting the fields. George Washington sent Benjamin Hawkins to serve as Indian Agent when the clash of these two cultures seemed imminent, but Hawkins could not ward off the inevitable. This part of the country was necessary to the manifest destiny of Thomas Jefferson, and was the proving ground for the fierce nationalism of Andrew Jackson.

The stories here are woven into an intricate tapestry: a story of the American frontier and a general, Jackson, who brutally and methodically moved a nation out so that another nation might survive. A story of the antebellum South where cotton was king. Here was one of the largest slaveholding regions of the country, and the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement. A story of rivers, and of water power, and of mills and industry.

It is estimated that at the time of first European contact, more than 90 million people inhabited North and South America. Anthropologists have grouped these Native American Societies, or American Indians, as they are known, into several culture areas. The Indian societies occupying land from the Atlantic coast west to central Texas were dubbed the Southeastern culture and included the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Creek people-the Creeks being the Indians who lived in the valleys and river bottoms of the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers.

The Creeks, like all other Native Americans, appear to have descended from Asian peoples who migrated across the Bering Strait, a 50-mile-long land bridge between Asia and Alaska, created during the Ice Age about 30,000 to 50,000 years ago. Those who made the crossing were not explorers or settlers or adventurers. They were simply hungry men and women following the game on which their livelihood depended. Over the centuries, their descendants spread out over the two continents, from Alaska to the tip of South America, from the Arctic Circle to the subtropics. People had to learn to live on frozen tundra, in forests, on grassy plains, and in arid deserts, in high mountains and in deep canyons, along rugged coastlines and lakeshores, and in fertile river valleys.

Some of these explorers ended up in the fertile valleys of the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers about 10,000 years ago. Known as the Paleo Indians, they were nomadic hunters of large mammals who roamed the region looking for food in a time when ice still covered much of the earth. Their daily routine centered on hunting. They traveled in small bands, or families, searching for the large animals of their day-mastodon, the giant bison, the mammoth. These animals provided them with meat and fat for food, skins for clothing, and bones for tools. The Indians stayed in one place for only a few days, eating the animals and plants in the area and moving on. They built shelters only if they found enough food in an area to last a few weeks or months.

By the Archaic Period, from 8000 b.c. to 1000 b.c., the ice had retreated, the climate had gradually warmed, and the large animals roaming the region between the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers had disappeared. White-tailed deer, boars, black bear, and many small animals, which can still be found today, became food sources. At this time Indians in the region were hunters and gatherers who utilized the new foods as well as shellfish and seasonal plants. They became dependent on rivers and their rich food sources. Nut-bearing trees were probably of great importance to these people, providing them with needed protein and fatty acids. The large stands of hickory and oak trees growing in the region were probably as important a food source as the abundant game.

The first steps to farming were taken when hunters began to understand more about the plants and animals they used for food. They possibly noticed that a plant would grow where seeds had fallen on the ground, or learned how to raise animals by taking care of young animals whose mothers they had killed. In the region between the Flint and Chattahoochee, it is known that during the Woodland Period, 1000 b.c. to a.d. 900, people planted sunflower, marsh elder, and goosefeet-plants considered weeds today. Eventually, squash and gourds and later corn and beans were cultivated. The Indians also learned to make pottery, which was a monumental step, as it was used to cook and store food and transport water. People began to live in villages at least part of the year. After thousands of years as hunters, these Woodland people no longer had to roam to obtain food. Farmers settled in one area for several years at a time and built villages near their cropland, living there as long as the crops grew well and the firewood lasted. Once the land became unproductive, the Indians moved to a new area.

During the Mississippian Period, a.d. 900 to European contact in the mid-1500s, the Indians built large villages, usually on rivers or steams, using the rich bottomlands for farming and the rivers and streams for transportation. Village areas surrounded huge, flat-topped temple mounds where social and religious ceremonies took place. The Mississippian Indians still hunted and gathered, but this culture discovered that the bottomland soils produced better crops and the periodic flooding that occurred restored the nutrients in the soil. They cultivated seed plants, pumpkins, beans and squash, probably tobacco, and especially corn. So important was the staple corn that the Mississippians gave it religious significance, connecting it to the king-gods, who led them. The great mounds they built, full of burial plots and artifacts, still stand, some protected as public property.

The

decade that followed their contact with Europeans brought cultural devastation

to the native people of the Southeast. The earliest known meeting between Southeastern

Indians and Europeans occurred in 1513 when a Spaniard name Juan Ponce de Leon

landed with his ship on the coast of Florida. Other Europeans followed. Hernando

de Soto and his band of Spanish explorers first set foot into the Flint River

Valley in 1540. These explorers were surprised to find an established culture

of people. But with these explorers came measles, tuberculosis, typhus, smallpox,

and other old world diseases, far worse than anything that could have been inflicted

upon the Indians with mere weapons or military force. Despite the tragic consequences

of disease, the survivors persevered and so began a 300-year-era of Indian,

black, and white interactions in the region.

The

decade that followed their contact with Europeans brought cultural devastation

to the native people of the Southeast. The earliest known meeting between Southeastern

Indians and Europeans occurred in 1513 when a Spaniard name Juan Ponce de Leon

landed with his ship on the coast of Florida. Other Europeans followed. Hernando

de Soto and his band of Spanish explorers first set foot into the Flint River

Valley in 1540. These explorers were surprised to find an established culture

of people. But with these explorers came measles, tuberculosis, typhus, smallpox,

and other old world diseases, far worse than anything that could have been inflicted

upon the Indians with mere weapons or military force. Despite the tragic consequences

of disease, the survivors persevered and so began a 300-year-era of Indian,

black, and white interactions in the region.

The Creek people are believed to be the southeastern descendants of the Moundbuilders of the Mississippian Period. These indigenous people of composite origin spoke a family of related languages referred to as Muskogean. They called themselves the Muskogee Nation-Muskogees or Muscogulges. (The word Muskogee, or Muscogee, signifies land that is wet or prone to flooding; "ulge" designates a nation or people.) But English-speaking white men called them Creeks because they lived and roamed the many rivers, streams, and swamps that ran through their territory-a territory that extended from the Atlantic to the Tombigbee River, through parts of Georgia, Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi.

By the eighteenth century the Creeks were the dominant tribe in a confederacy with a membership of about 30,000. The confederacy occupied most of what are now the states of Georgia and Alabama. After the Cherokee, the Creeks were the most powerful grouping of Native Americans south of New York.

The Creek Nation included approximately 60 towns and was divided into two geopolitical divisions, which the Europeans called the Upper Towns and Lower Towns. Forty Upper Towns lay along the Tallapoosa-Coosa-Alabama River System and 20 Lower Towns were scattered on the Ocmulgee, Flint, and Chattahoochee rivers of Georgia. This division predated trading relations between the Creeks and the British Colonies, but it originated with the relative position of the two main trading paths that linked the Creeks with South Carolina: the Upper Creek Trading Path and the Lower Creek Trading Path. These two divisions differed not only geographically, but also politically. The Creeks respected their kinship with each other but held separate councils, claimed separated territories, and very often pursued different foreign policy-a difference that would ultimately effect their survival. Besides that, Creeks also divided their towns into two types-red, or war towns, and white, or peace towns.

After the American Revolution (1775-1783), the Creeks, who had supported the British, were faced with land-hungry American settlers eager to push into Creek territory and an American government somewhat intent on manifest destiny. In 1796, President George Washington appointed Colonel Benjamin Hawkins as Indian Agent on the Flint River. Hawkins's philosophy to integrate the Indians into the white culture by teaching them the skills of modern farming and industry was noble but difficult to implement. Some Creeks, mostly in the Lower Towns, realized the advantages of cooperating with the Americans, but other, younger Creeks, mostly living in the Upper Towns, rejected contact with whites and the consequent abandonment of their Indian culture.

All Creeks resented the relentless encroachment on their land. Encouraged by the Spanish in Florida and the British in Canada, who promised to provide arms and supplies, many Creeks prepared for war against the United States, which was now building roads from Georgia into the Alabama settlements. Tecumseh, a Shawnee Indian chieftain from the northern tribes, conceived a plan to organize all tribes from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and force out the white man. In 1811, he visited the Creeks, including Red Eagle, leader of the militant Red Sticks (named as such because they painted their war sticks a bright red) to recruit warriors and gain support for his campaign. As Tecumseh stirred their fears and hatreds, the Creek Nation became more divided and the threat of civil war loomed between the Upper and Lower tribes.

Desultory raids on white settlements along the American border by the Upper tribes widened the split within the Creek Nation. Finally, on August 30, 1813, Red Eagle and 1,000 Creek followers of Tecumseh descended upon Fort Mims, a white stronghold located about 40 miles from Mobile, butchering about 500 men, women, and children.

So began the Creek War of 1813-1814. In the long history of Indians in North America, the Creek War was the turning point in their ultimate destruction. The irreversible step toward obliterating tribes as sovereign entities within the United States now commenced. The Creek Nation would be irreparably shattered. All other tribes would soon experience the same melancholy fate.

As the Creek warriors descended upon Fort Mims little did they know that this would be the death knell of the Creek Confederacy, for it set U.S. General Andrew Jackson on his course to enlarge the territory of his newly found nation while annihilating that of the Creek Indians.

Jackson was a child of the American Revolution. Born in 1767, he was a veteran of the war and the victim of intense personal suffering by the time he reached the age of 15. He grew up with a loathing of the British, a determination that America would prosper, a hatred of the Spanish, and a paternalistic attitude towards the Indians.

With the massacre at Fort Mims, Jackson recognized that his long-awaited opportunity for military glory had arrived. With 2,500 volunteers and militia authorized by Governor William Blount of Tennessee, Jackson set out from Nashville with one of four armies that would enter the Creek Nation. The strategy was to kill the Red Sticks, burn their villages, and destroy their crops. As they marched south, the army would build forts about one day's march apart in order to divide the Creek Nation.

Although plagued by desertions, lack of food and supplies, and demands from Governor Blount to abandon the expedition, Jackson drove forward. By the close of 1813, he had battled twice with the Creeks. On March 27, 1814, on the Tallapoosa, where the winding river sweeps in a great loop at Horseshoe Bend, he struck them with fury. By Jackson's side were Indian fighter Davy Crockett and a young officer named Sam Houston. When the battle ended, U.S. troops had slain more than 700 warriors, breaking the spirit of Creek resistance. Creek prophets had said they could never be driven from the ground at Horseshoe Bend. But most of the defenders were dead and the homeplace lay in ruins.

After Horseshoe Bend, the Creek War was all but over. Although the federal government sent army General Thomas Pinckney and Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins to arrange a peace treaty with the Creeks, Jackson dictated the terms at the negotiations. From them, he demanded the equivalent of all expenses incurred by the United States in prosecuting the war. By Jackson's calculation this came to 23 million acres of land-more than half of the old Creek domain, and roughly three-fifths of the present state of Alabama and one-fifth of Georgia.

By this treaty, the entire Creek Nation, even the Indians who had fought on Jackson's side, had to pay the enormous indemnity. All were required to remove themselves from their land and become wards of the federal government. The treaty removed the threat of attack from the borders of Tennessee and Georgia. It also confined the Creeks to a manageable area where they could be watched and guarded and where they were separated geographically from the evil influence of the Spanish in Florida and Indians who had fled.

At Jackson's urging, the boundaries were drawn and the land sold to settlers as quickly as possible-a measure that would ensure the security of the frontier.

Horseshoe Bend was not the end of Jackson's conflict with Indians, for now he would go after the Seminoles in Florida. But the Creek War and the Treaty of Fort Jackson set up a pattern of land seizure and removal that ensured the ultimate destruction of not only the Creek Nation, but of all Indians throughout the South. And the man responsible was Andrew Jackson.

With the land cessions and subsequent removal of the Creeks, settlers rushed in, many times establishing a white settlement around what had been a frontier fort or on or near the location of what was once an Indian town. Most settlements grew up along the banks where river crossings were easier, or at an intersection where major Indian paths converged. No matter what the culture or purpose people tend to look for the same traits in settling a village or town: land near water, land on high ground for protection, land with good fertile soil for growing crops. The Indian town of Chehaw became Albany. Pucknawhitla became Burgess Town, which became Fort Hughes, which became Bainbridge. Chemocheechobee became Fort Gaines the fort, which later became Fort Gaines the town.

But white settlers were more industrial-minded than the Creeks. Towns grew up around the gristmills that were built on rocky streams. Towns grew up around river landings where area farmers brought their cotton for shipment to Apalachicola. Towns grew up wherever the tracks of a railroad terminated.

The destiny of much of the Flint and Chattahoochee river valleys was bound in cotton. King Cotton. In fact, cotton was one of the first crops specified to be grown in the Georgia colony when James Oglethorpe and the colonists first arrived at Yamacraw Bluff in 1733. And cotton was the reason planters and farmers flocked to the Flint River Valley as soon as the Indian threat lessened. Cotton had sorely depleted the soils in the eastern part of the state and beyond in the Carolinas. The Flint River Valley was land that had never been touched by cotton. At first, cotton, which was labor intensive, was only profitable for the very large planters who owned hundreds of slaves supplying the labor needed to plant, pick, and hand remove the seeds from the short staple fiber. But after Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin in 1793, the economics changed. The gin cleaned cotton as fast as 50 persons. Cotton became profitable to produce on small farms as well as large slaveholding plantations. Both types of farmers grabbed up the "Land Between the Rivers," and by 1860 Georgia was the world's largest producer of cotton, with much of that production coming from the Flint River Valley.

But the Civil War did much to change the agricultural economy of the region. Plantations were divided into tenant farms. Farmers were growing corn, tobacco, and peanuts, but cotton still ruled. Farmers ignored agrarian leaders across the South who warned of cotton's effect on the soil and the farmer's dependency on cash crops.

By the 1920s, severe erosion, soil depletion, the boll weevil menace, and the Depression wreaked havoc on the state's agricultural economy. Between 1920 and 1925, 3.5 million acres of cotton land were abandoned throughout Georgia and the number of farms fell from 310,132 to 249,095. It would take new ways of farming, new farm programs resulting from President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal Programs, and a world war to turn the agricultural economy around in the region, as well as in the rest of the South.

By the time Plains peanut farmer Jimmy Carter was elected President of the United States in 1976, peanuts and soybeans-combined with traditional row crops, such as corn, cotton, wheat, and vegetables-were important crops grown in southwest Georgia. Dairying as well as cattle, hogs, and pigs also became important to the area's agricultural economy.

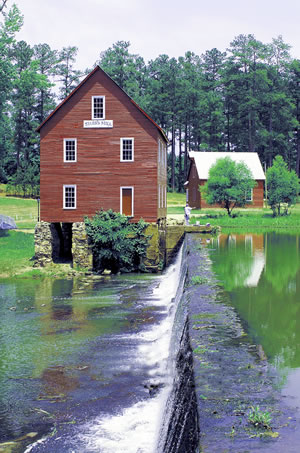

Along

the Flint River and its tributaries settlers built gristmills, the first real

industries of the area. Until the early twentieth century, most mills used water

from nearby streams to power gears and machinery. The hilly Piedmont of the

fall line section of the river, where the water rushes over rock outcroppings

and shoals, created ideal locations for mills.

Along

the Flint River and its tributaries settlers built gristmills, the first real

industries of the area. Until the early twentieth century, most mills used water

from nearby streams to power gears and machinery. The hilly Piedmont of the

fall line section of the river, where the water rushes over rock outcroppings

and shoals, created ideal locations for mills.

Today, many times only place names, such as Lee's Mill, Terrell Mill, and Mundy's Mill in Clayton County, remain. In some places, such as Flat Shoals, ruins can be spotted. At a few sites, a structure may still stand, such as Starr's Mill in Fayette County. At one time all of these mills were important community centers. Farmers traveled for miles to the nearest mill to grind grain, saw timber, hull rice, or gin cotton. They fished the pond, swapped news and stories, or picked up some supplies as they waited their turn to grind their corn. Many times a town grew up around the mill itself.

Where there was water power and plenty of cotton, it was only natural that textile mills would be built. A number of settlers came to Upson County from northern states for the express purpose of establishing textile mills. The first cotton mill in Upson County, Franklin Factory, was built on Tobler Creek in 1833. A total of four textile mills, all water-powered, were built before the Civil War, making Upson the center of the textile industry in middle Georgia.

The textile mills in Thomaston, as well as the mills in Columbus on the Chattahoochee, were extremely important to the Confederacy during the Civil War, making such items as gray uniform tweed, osnaburg cloth, cotton duck for tents, and cotton jeans. One of the goals of the Union Army as it swept through Georgia in the waning days of the Civil War was to destroy as many mill sites as possible. On April 16, 1865, in one of the last major land battles of the war, 13,000 Federal calvalry troops invaded Columbus from Alabama and burned all of the war-related mills, warehouses, and foundries. They then moved across the land-burning plantations and destroying railroads-to the Flint, crossed it via the old Double Bridges and completely destroyed all four textile plants and several gristmills in Upson Country.

The textile industry, however, was one of the few industries in the South to rebound quickly after the war. New mills were built in both Columbus and Thomaston. As the technology of mill building changed-turbines connected to mechanical gears-the mills no longer had to be close to the rivers to receive their energy supply.

More than 300 years ago a Creek Indian village existed near what is now Albany. It was called Thronateeska. The word in the Creek language means "flint picking up place" and, over time, the name came to be applied to the river that ran by the village. This river, its watershed, its physical alliance with the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola rivers, and its history all combine to tell a fascinating story with universal themes-a story of people, of Georgia, and of America.

Go back to previous page. Go to The Flint River contents page. Go to Sherpa Guides home.

[ Previous Topic | Next Topic ]