Southern

Sierra

Southern

Sierra South of Yosemite National Park and west of the Sierra Nevada crest, nearly 3.5 million acres of trails, lakes, canyons, and high country vistas offer almost every recreational opportunity possible in this mountain range. The wildernesses in the Southern Sierra are among the most popular hiking destinations in the world, rivaling even Yosemite. But visitors have lots of options: scenic driving, whitewater rafting, bird-watching, photography, camping, backpacking, fishing, swimming, skiing, snowshoeing, and picnicking are available in some of the most beautiful places in the range. The elevations go from about 900 feet in the western foothills to more than 14,000 feet at the crest, so there is a lot of diversity in the southern ecosystems.

The Southern Sierra begins with the 1.3-million-acre Sierra National Forest, just south of Yosemite. Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks cover a combined 856,000 acres southeast of the Sierra forest. The 1.2-million-acre Sequoia National Forest is at the southern end of the range. In case there is confusion, the Sierra forest is a part of the Sierra Nevada range—Sierra within the Sierra. The Sequoia forest is separate from Sequoia National Park.

The two public agencies—the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service—manage land quite differently from each other. The Forest Service, which is part of the Department of Agriculture, has historically allowed grazing, mining, logging, hunting, and off-road vehicle recreation in addition to hiking, camping, and other recreation. Land managed by the Park Service, which is part of the Department of Interior, is considered a wildlife sanctuary where commercial enterprises such as grazing, mining, and logging do not generally take place.

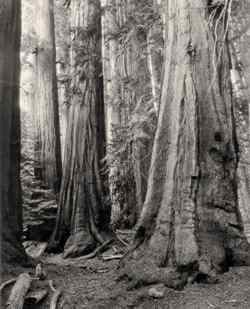

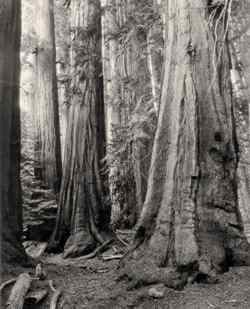

The

Sequoia park and forest contain most of the giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron

giganteum) left in the world. Sequoia National Park has the largest

tree in the world in the ancient grove at Giant Forest. The General Sherman

tree, estimated to be more than 2,000 years old, has a circumference of

about 103 feet at ground level. At 275 feet tall, it is not the tallest

tree—the coastal redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) has been measured

at more than 380 feet tall near the California coast. But the weight of

the Sherman tree is estimated to be almost 1,400 tons, easily making it

the largest living tree on earth.

The

Sequoia park and forest contain most of the giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron

giganteum) left in the world. Sequoia National Park has the largest

tree in the world in the ancient grove at Giant Forest. The General Sherman

tree, estimated to be more than 2,000 years old, has a circumference of

about 103 feet at ground level. At 275 feet tall, it is not the tallest

tree—the coastal redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) has been measured

at more than 380 feet tall near the California coast. But the weight of

the Sherman tree is estimated to be almost 1,400 tons, easily making it

the largest living tree on earth.

Kings Canyon National Park, which the National Park Service manages under one administration with Sequoia National Park, has an interesting natural distinction as well. The Kings River canyon is the deepest river canyon in the United States. It is about 8,000 feet deep—deeper than the Grand Canyon in Arizona.

The two forests of the Southern Sierra, the Sierra and the Sequoia, have a combined 10 wildernesses. Both share wildernesses with the Inyo National Forest to the east. The Sierra, for instance, shares the John Muir and the Ansel Adams wildernesses, while Sequoia shares the Golden Trout and South Sierra wildernesses with Inyo. Both the Sierra and the Sequoia contain pieces of the Monarch Wilderness.

In the Sierra forest, a chain of hydroelectric lakes northeast of Fresno provides power and recreation. The hydro construction began around the turn of the century as Southern California Edison searched for ways to supply growing Los Angeles with power. The hydro chain is one of the oldest in California.

But most people do not think of electricity when they see these human-made lakes. They think of fishing and boating. Huntington and Shaver lakes are stocked with rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis). A sailing regatta is held every summer at Huntington.

Just south of the hydro chain, the Kings River provides kayaking and whitewater rafting opportunities for visitors. The middle and south forks of the Kings are designated for federal protection under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Combined with the Merced River, which flows out of Yosemite to the north, the Sierra has 224 miles of Wild and Scenic rivers.

Archaeologists say western Piute, Mono, and Chuckchansi tribes came to the Sierra forest to spend summers about 5,000 years ago. Loggers began working in the area during the late nineteenth century. The warmer seasons are longer here compared to the Central and Northern Sierra, so human activities could begin earlier and end later in the year than in most other places in the mountain range.

The farther south visitors travel, the milder the climate becomes in the lower elevations of the Sierra. The peaks and high country still get pasted with big storms and a lot of snow, but the Southern Sierra below 5,000 feet has short winters and long, dry summers. Consequently, spring can come as early as March in some foothill areas, even though the wildflowers do not start blooming until July in many high country meadows.

Plants that would normally occur at 3,000 feet farther north in the mountain range begin appearing at 5,000 feet and up in the Southern Sierra because they can adapt to the drier conditions at these elevations here. The foothill vegetation of chaparral, such as bush poppy (Dendromecon rigida) or poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum), will occur at greater elevations on the western slope in the Southern Sierra than it does in the Central Sierra. Many of the animal communities also range higher in this part of the Sierra.

Among the more important parts of the animal community in this part of the range is the bat, which can be found in many parts of the Southern Sierra. With few natural enemies—owls and some hawks sometimes hunt for them—they are voracious consumers of insects. A bat can eat its own weight in insects during one night feeding. There are more than a dozen species in this area of the Sierra, including the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) around Kings Canyon National Park and the big-eared bat (Plecotus townsendii) in Sequoia National Forest.

Farther south, the Kern River presents an intimidating flow of water each spring, particularly in the dangerous upper reaches where rapids are often too turbulent even for experienced whitewater boaters. Between the upper reaches and Isabella Lake, just above Bakersfield, the river annually drowns about eight people. The river drops 28 feet per mile, a steep run compared to the Mississippi River, which averages about 2 feet per mile. In the hands of professionals, whitewater kayaking and rafting can be more exciting here than any other place in the Sierra. But this is no place for novices.

The cultural history of this region includes mining in the nineteenth century. Mining is what opened up one of the more stunning locations in the Southern Sierra, Mineral King in Sequoia National Park (see page 282). James Crabtree claimed the White Chief mine in 1873 and started a rush of miners who searched for silver. They did not find much silver, but they were successful in building a road that would eventually be extended to picturesque Mineral King, which is a glacial canyon up against the western divide of the Sierra. The road is 24 miles of winding, gut-turning switchbacks. The payoff at the end of this unsettling journey is well worth the trouble, but motorists should drive this road carefully and slowly.

Read and add comments about this page