Bucks

Lake Wilderness/Recreation Area

Bucks

Lake Wilderness/Recreation Area [Fig. 10, Fig. 11, Fig. 12] The timber industry has shaped the Plumas National Forest's 1.1 million acres since it was established in 1905. For instance, in 1987 alone, loggers cut enough trees to build 19,000 three-bedroom homes. Plumas trees also help support another industry—Christmas tree sales. About a third of California's Christmas trees come from the Plumas. And they are white firs (Abies concolor).

But logging is not common in every part of the forest. Bucks Lake Wilderness, for instance, does not have logging. Logging is forbidden in any wilderness. Federal law passed in the 1960s banned logging in designated wilderness areas. No mechanized activities are supposed to take place, including bicycle riding. Some exceptions are allowed for such activities as snow measurement, which involves the use of helicopters to reach snow fields.

The Feather River is the main stream in the Plumas. Its 100-mile Middle Fork is designated as wild and scenic, though the final third of the river above Lake Oroville is inaccessible to all but the bravest kayakers and hikers.

The North Fork of the river has eight hydroelectric powerhouses on it between Oroville and Bucks Lake Wilderness. The South Fork is probably the least known for natural beauty, draining smaller watersheds. It winds through Little Grass Valley Reservoir before joining the Middle Fork at Lake Oroville.

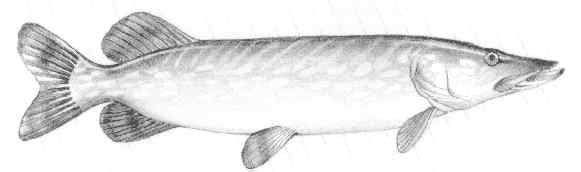

The lakes and streams of Plumas are well known for their abundance of fish. Several kinds of trout are found in these waters. Among them are rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), brown trout (Salmo trutta), and the rarer golden trout (Salmo aguabonita), a species that evolved in the Southern Sierra earlier this century after brown trout were planted in the Kern River and other places.

Bucks

Lake Wilderness/Recreation Area

Bucks

Lake Wilderness/Recreation Area [Fig. 12] People come to the Bucks Lake Wilderness for the views. On a clear day, hikers can see Lassen Volcanic National Park, 40 miles away, somewhere near the northern edge of the Sierra Nevada. The sight is worth the considerable effort it takes to get many miles into this wilderness.

But the views of red fir (Abies magnifica), brush fields, and delicate mountain meadows are also worth it. This small, 21,000-acre wilderness has a vibrant diversity of plant life, but not many lakes. Elevations range from 2,000 feet in the Feather River Canyon, to 7,017 feet at Spanish Peak.

Plant life includes the common horsetail (Equisetum arvense) and sago pondweed (Potamogeton pectinus), both found in streams and bogs where the water moves slowly or stands still. The Sierra shooting star (Dodecatheon jeffreyi), with its pink and crimson petals, is found throughout the lower elevations of the area along with the yellow and purple farewell-to-spring (Clarkia viminea), which owes its name to its later appearance in the warmer months.

The red fir, occurring at ridgelines and rocky, high-elevation fields, thrives in Bucks Lake Wilderness in moist areas. The dark blue-green needles are aromatic and were used by early mountaineers as bedding.

In the high elevations of Bucks Lake, many red fir lose their tops in blizzards that batter the area during winter. The damaged trees will provide nesting cavities for chickarees (Tamiasciurus douglasii), alpine chipmunks (Eutamias alpinus), and martens (Martes americana).

Because there are not many other food-producing plants at 7,000 feet, the red fir is also home to several kinds of woodpeckers, pygmy nuthatches (Siita pygmaea), and brown creepers (Certhia familiaris) on its trunk. Seedeaters flock to the tree in autumn when cones mature.

The Bucks Lake Pluton, the massive granite formation beneath the area, is Cretaceous, or about 130 million years old. In this part of Plumas National Forest, the granite is striking in steep canyons and outcroppings.

At the southwestern edge of the wilderness, and about 10 miles west of Quincy, is Bucks Lake at 5,155 feet in elevation. The lake, a hydroelectric lake, has a surface area of 1,827 acres with 14 miles of shoreline.

Bucks Lake was named by one of the first settlers in Bucks Valley, Horace "Buck" Bucklin, who came into the area from New York in 1850. The lake is located in a valley known for almost 80 years as Bucks Ranch.

In 1925, the Bucks Creek Project was undertaken by the Feather River Power Company to produce electricity in the area. Part of the project, Bucks Dam, was completed in 1929. Title passed to the Great Western Power Company the same year, and later to Pacific Gas and Electric Company. About half of the shoreline is now owned by Pacific Gas and Electric and the other half is under the management of the Forest Service.

The recreation area is directly adjacent to the southwestern boundary of the wilderness. It is not included in the wilderness because it would be subject to restrictions that would not allow motorized vehicles or any other kind of mechanization.

Fishing, which is regulated by the California Department of Fish and Game, is a popular activity at the recreation area. Bucks Lake and surrounding streams and lakes support rainbow (Oncorhynchus mykiss), brown (Salmo trutta), and Eastern brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis). Bucks Lake is stocked with rainbow trout annually.

[Fig. 12(1)] The Summit-Bucks Creek Loop Trail provides the best views of the Bucks Lake Wilderness. It starts at Bucks Summit and leads 2 miles through meadows and forested areas.

When the trail reaches the pavement, turn right and take the Bucks Creek Trail 1.8 miles back to Bucks Lake Road and continue 0.25 mile to Bucks Summit. This trail goes through the Whitehorse Campground, and it can be used for hiking and mountain bicycling.

[Fig. 12(2)] The Mill Creek Trail leads to views of the Bucks Lake Wilderness. The trailhead and first mile are on Pacific Gas & Electric Company land, where recreation is permitted. Camping is allowed along the eastern shore of Bucks Lake, for those who want to stay the night by the lake after the hike.

For more adventuresome hikers, the trail continues into the wilderness for several miles. Horses are allowed on this trail, so hikers must keep their eyes open and yield.

[Fig. 12(3)] This is a good one for families. It is a short hike with some good fishing for the various kinds of trout. The box canyon has some nice picnic areas, but there are no developed facilities. It will take about 90 minutes to hike this trail.

[Fig. 12(4)] This one may be better as an overnight trip. The elevation gain alone is more than 0.5 mile, and it is also a long haul. The round trip is 13 miles—not that difficult for a fit, experienced hiker, but a challenge for most others.

The trail has excellent campsites along the way, along with splendid views. The sights include Lassen Volcanic National Park to the north.

[Fig. 12] The Feather River drains about 100 streams in the Plumas National Forest, stretching across most of the more than 1 million acres. The river is formed by three distinct branches—the North, Middle, and South forks.

The North and Middle forks are the focus of most recreation on this river. The North Fork is known for its hydroelectric powerhouses. About 100 miles of the Middle Fork have protection under the federal Wild and Scenic River Act. The South Fork does not carry the same volume of water and is not the same kind of attraction as the other two forks.

Though only the Middle Fork is considered wild and scenic, the North Fork could lay claim to being scenic as well. Along the North Fork of the Feather River, about 3 miles northwest of Oroville, anyone who has traveled through the Stanislaus National Forest or the Sierra National Forest will see a familiar site: a Table Mountain, created by a lava flow going down an ancient streambed.

Table Mountain is the proper name given to these geologic features. The lava flow near Oroville occurred about 50 million years ago, paving the streambed with basalt. The hardened basalt survived the erosion process over time and now stands as a flat-top mountain.

Along State Highway 70, there is evidence of rocks much older than the Table Mountain. Slates and schists, which probably were deposited as marine layers in the Pacific Ocean 200 million years ago, can be found along road cuts on Highway 70.

For a windshield tour of the upper watershed, the Feather River Scenic Byway offers spectacular views and countless points of cultural, geologic, and historical interest. The scenic byway begins 10 miles north of Oroville on State Highway 70, meanders east to US Highway 395, cuts through deeply carved canyons, tunnels through huge boulders, and races alongside the rugged North Fork of the Feather River. The Feather River Scenic Byway was officially dedicated in October 1998.

The Middle Fork is probably the most famous and revered by naturalists. It was one of the first nationally designated wild and scenic rivers in the United States.

The Middle Fork runs from its headwaters near Beckwourth to Lake Oroville, and it has three, distinct zones: recreation, scenic, and wild. Any part of the river or its canyon may be rugged and difficult to access.

In the wild zone, steep cliffs, waterfalls, and huge boulders discourage most people from trying to float or hike. While the scenic zone is less rugged, it still requires great preparation and skill. Even the recreation zone requires preparation and caution, especially in spring. In spring months, the volume of water coming down the Middle Fork alone would fill most of the streams in the southern part of the Sierra.

The lower part of the Middle Fork begins with Bald Rock Canyon Wild River Zone, extending from Lake Oroville (900 feet elevation) upstream for about 5.4 miles, through Bald Rock Canyon to the junction of an unnamed drainage on the east side of the river, about 7 miles south of Milsap Bar Campground (1,500 feet elevation). The wild and scenic lower parts of the Middle Fork should not be used for canoeing or rafting.

The next section of the Middle Fork begins as Milsap Bar Scenic River Zone, about 3.6 miles long, extending from the upper limit of Bald Rock Canyon Wild River Zone upstream to an area just below the English Bar Scenic Zone and Recreation Zone.

The English Bar Zone is more gentle. From Clio down to Quincy-La Porte Road, canoeing and rafting are possible during spring. When flow drops off later in the summer, air mattresses and inner tubes are the most common mode of travel. Whitewater rafting takes place downstream, below Lake Oroville. For more detailed information on the sights and dangers of rafting the Feather, contact the Plumas National Forest, phone (530) 283-2050.

Perhaps the most spectacular viewing is at the Feather Falls Scenic Area,

near the old town site of Feather Falls. Granite domes and waterfalls are

the big attractions. Visitors can see the sights from the Feather Falls

National Recreation Trail, a

challenging 10-mile round-trip hike (2,500-foot elevation gain). The hike

will take several hours round-trip, and markers are provided every 0.5 mile

to keep hikers aware of their progress.

There are no services along this trail—no refuse containers or restrooms. The trailhead has a vault toilet, water, and a refuse container. Otherwise, pack it in and pack it out is what the Forest Service advises. Carry food and lots of water. The reward at the end of the hike is the 640-foot high Feather River Falls, the sixth tallest waterfall in the United States. The falls are most accessible from early April to October.

Another attraction is Bald Rock, part of a granitic pluton formed about 140 million years ago. The rock is only 0.25 mile from a parking area. The views of the Great Central Valley are wonderful. Native Americans ground acorns on Bald Rock and legend has it that Uino, a Maidu monster, protected the Middle Fork of the Feather River from a vantage point high atop Bald Rock.

Take a little closer look around the river and see the California newt (Taricha torosa) and the Pacific treefrog (Hyla regilla) in the lower elevations. The only aquatic salamander found in the higher elevations is the long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum), and it lives around the Feather River, hiding under rocks in the quieter parts of the river.

The quieter water also allows insects, such as the water striders (Gerris remingis), to develop and provide food for fish. Along the shore, the caddisflies (order Trichoptera), mayflies (order Ephemeroptera), and scorpionflies (order Mecoptera) provide food sources in their larval stages for many amphibians and other creatures.

[Fig. 12(5)] It takes about 90 minutes of hiking on the McCarthy Bar Trail to get into some fine fishing. It is fast walking, though, because the trail goes downhill. It takes closer to three hours to hike out, because of the steep climb out of the canyon.

People often like to stop and camp along the river, sleeping to the sound of rushing water in one of Northern California's premiere rivers. The trout fishing is excellent in the cold water, which is rushing by after melting perhaps 24 hours earlier from a high Sierra snowpack at 7,000 or 8,000 feet.

Two other trails, the No Ear Bar and the Oddie Bar, are almost identical to the McCarthy Bar Trail. They may be a little easier to find, but they do not have as many campsites as McCarthy.

[Fig. 12(6)] Little Grass Valley Lake Recreation Area offers people a wide variety of outdoor experiences at an elevation of 5,046 feet. The lake covers a surface area of 1,615 acres and has a shoreline of 16 miles. The lake holds 93,000 acre-feet of water.

Besides fishing, boating, and camping—the three main attractions at many Plumas recreation spots—this area provides some bird-watching opportunities. Look for the common loon (Gavia immer), double-crested cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus), and the Wilson's warbler (Wilsonia pusilla). All are known for nesting on the western slopes in this part of the Sierra, principally because of the water and cooler temperatures of the Northern Sierra.

The evening grosbeak (Hesperiphona vespertina) and other finches, such as the purple finch (Carpodacus pupurens) and the casin finch (Capodacus cassini), are found around Little Grass Valley Lake.

One of the unusual features of the area is the appearance of the brilliant red snow plant (Sarcodes sanguinea) during May, June, and July. These flowers grow at elevations between 4,000 and 8,000 feet and begin blossoming on the heels of melting snow. Against a carpet of pine needles, this saprophyte catches the eye instantly.

Before the arrival of European settlers, this valley was inhabited by migrating bands of Maidu Indians. They spent the summer in Little Grass Valley hunting and gathering berries and acorns away from the heat of the Great Central Valley to the west.

With the discovery of gold and the rush of miners into the gold-rich country, Little Grass Valley became a supply post. Ranchers began grazing sheep and cattle in the lush meadows, and they supplied meat and farm produce to the adjacent mining communities of LaPorte, Gibsonville, Howland Flat, Port Wine, and others.

[Fig. 12(7)] Horseback riders, bicyclers, and hikers are likely to encounter each other on this trail, which runs along the north shore of Little Grass Valley Lake. People are encouraged to yield to larger, faster modes of transportation—namely, the bicyclers and the horseback riders.

No off-road vehicles are allowed on this trail.

Lake

Davis

Lake

Davis [Fig. 13] Fishing, boating, camping, bike riding, and hiking are all available at Lake Davis, but this lake is also known for birding. Many of Plumas's nearly 300 species are at Lake Davis.

Birds such as the warbling vireo (Vireo gilvus) are best observed by listening first. They're found in the lodgepole fir belts and in such trees as the Lemmon willow (Salix lemmonii), which are near the water. The vireo's throaty "zree" can be sustained and repeated many times.

The red-breasted nuthatch (Sitta canadensis) is another that can be heard before being seen. It can be heard repeating its high nasal "na," faster and faster when it becomes agitated. It sounds like a small trumpet.

Other birds worth watching are the hairy woodpeckers (Denrocopus villosus), American white pelicans (Pelicanus erythrorhynchus), osprey (Pandion haliaetus), western tanager (Pranga ludoviciana), and, of course, the seemingly ubiquitous wood duck (Aix sponsa). For a free list of birds common to the area, contact the Plumas Audubon Society, PO Box 3877, Quincy, CA 95971, or phone (800) 326-2247.

Biking

is another favorite activity around Lake Davis. In many parts of the Plumas,

including Lake Davis, cyclists can use abandoned logging roads, areas designated

for off-highway vehicles, and some backcountry roads. These areas are open

to bikers and provide a good cross-section of terrain and topography. Stay

on the roads, and don't cut the switchbacks.

Biking

is another favorite activity around Lake Davis. In many parts of the Plumas,

including Lake Davis, cyclists can use abandoned logging roads, areas designated

for off-highway vehicles, and some backcountry roads. These areas are open

to bikers and provide a good cross-section of terrain and topography. Stay

on the roads, and don't cut the switchbacks.

The Lake Davis Loop is perhaps the best-known bicycling trip in the area, featuring a flat, easy loop around Lake Davis. Points of interest include Jenkins Sheep Camp and lake vistas. Cyclists can also enjoy bird and wildlife viewing. Vehicle traffic may be heavy on weekends.

The loop is 18.4 miles at an elevation just below 5,800 feet. Average riding time is two hours. The surface is gravel for 6.1 miles and paved for 12.3 miles. To reach the trailhead, from Highway 70 near Portola take Lake Davis West Street (County Road 126) 7 miles to Lake Davis Dam. Park at the information kiosk.

But bird-watching and bicycling are not the only attractions. Fishing may be more popular. The lake is stocked and some natural trout occur in this 84,000-acre-foot body of water. The dimensions of the lake—maximum depth, 105 feet; surface area, 4,000 acres; and shoreline, 32 miles—make it small enough for anglers to learn quickly. Yet it is large enough to allow a lot of water recreation, which does not include water skiing.

Varieties of trout include rainbow (Oncorhynchus mykiss), brown (Salmo trutta), and Eagle Lake (Salmo eagllia). Brown bullhead (Ictalurus nebulosus) also are found in this cold-water lake. Fishing is regulated by the California Department of Fish and Game, not the U.S. Forest Service.

[Fig. 13] The Plumas-Eureka State Park offers gold-rush history, cross-country skiing, and natural history.

The geologic history runs back 400 million years. About 400 yards south of the entrance to the campground of this state park is evidence of volcanic silicic ash and breccia, which are probably predated only by 400-million-year-old slates and sandstones in the area. This is truly a geologic time capsule for those patient enough to inspect the rock formations.

At 7,447-foot Eureka Peak, hikers can see where dolomite flowed into uplifted folds of older rock. The older rock, such as chert and limestones, is also present in formations that probably originated as marine sediments more than 400 million years ago.

But, like many places in this part of the Sierra, this area is more known for its recent history—the gold rush. Gold was found on the east side of Eureka Peak on May 23, 1851, when the mountain was known as Gold Mountain.

The discovery by nine miners triggered widespread gold fever. Several operators and many companies dug 62 miles of shafts. British mining experts figured ways to remove the rich ore from within the mountain.

At one point, three stamp mills were in operation at various locations on the mountainside, but the Mohawk Stamp Mill became the main mill of the time. Built in 1876 at a cost of approximately $50,000, the Mohawk contained 60 stamps, each weighing from 600 to 950 pounds. The stamps could crush more than 2 tons of ore every day.

Today, visitors can go to the main museum, originally the miners' bunkhouse, to learn about natural and cultural history of the park. Across the street, the old Mohawk Stamp Mill still stands.

Along with the history, the park offers a variety of wildlife viewing opportunities. In the 5,500 acres of the park, visitors may see the pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus), the largest woodpecker in the Sierra. It most likely would be found in a fir tree—generally a Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) or a white fir (Abies concolor)—pounding while swinging its head in an exaggerated, 8-inch arc.

The lavender feathers of the smallest hummingbird in North America, the calliope hummingbird (Stellula calliope), also can be seen. The best viewing months are between May and August when the hummingbirds visit white-leaf manzanita (Arctoostaphylos viscida) or currants (Ribes) for nectar.

Madora and Eureka lakes, as well as Jamison Creek, offer fishing opportunities. Rainbow trout (Salmo gairdinerii) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) can be found at Madora. Eureka has only brook trout (Salvelinus fontialis). The creek has mostly rainbow trout. Various smaller alpine lakes have species of golden trout (Salmo aguabonita). The golden trout developed into a separate species in the Southern Sierra several decades ago after rivers and lakes were planted with brown and rainbow. The golden trout were then planted in other areas.

Cross-country skiing is another favorite activity in the park. There is one developed ski trail and numerous other alternatives for those who like to combine mountaineering and skiing.

Lakes

Basin Recreation Area

Lakes

Basin Recreation Area [Fig. 14] Take your pick: Gold Lake, Squaw Lake, Haven Lake, Long Lake, Rock Lake, Jamison Lake. There are more than a dozen lakes with fishing, boating, swimming, and camping being the main attractions.

Lakes Basin is where many outdoor enthusiasts have seen nesting bald eagles (Haliaetus leucocephalus), endangered birds known to do their share of fishing.

Around the lake, hikers will find an interesting and characteristic feature of the Northern Sierra—solifluction terraces. They are saturated parts of the soil that are creeping downslope and become hung up on small terraces. The soil begins folding and piling up.

Plants, such as sedges and alpine willow (Salix petrophila), begin growing and solidifying the saturated soil. Small ponds form in the depressions of these terraces, usually as the snow melts.

The basin area is a gem of the Plumas National Forest, archaeologists say. It may have been the summer hunting and fishing ground of a tribe related to the prehistoric Martis people or the Great Basin or Central California native Americans. Visitors can see petroglyphs—some dating back as far as 10,000 years—near the Lakes Basin Campground.

The area's natural history has been studied extensively. Fossil leaves found in Gold Lake were dated at 19 million years old, and experts have concluded the area climate was tropical at the time. A summer rain season, which does not exist now, contributed to the 35 to 40 inches of annual rainfall at the time. Trees that are now common in the southeastern United States were found in this area at that time.

For anyone interested in the volcanic history of the area, Frazier Falls is a place where the top of a 2-mile-thick formation of volcanic rock begins. While most folks may be absorbed in the 176-foot vertical drop of the falls, just northeast of Gold Lake, the volcanic sandstone and andesite can be seen just west of the picnic grounds at the falls. Since the depth of this widespread formation varies so greatly, some geologists believe it might have been a massive volcanic eruption that was tilted on its side by the active California geology of the past.

The Lakes Basin hike is the tour of choice for most hikers, though it is strenuous. It features the Sierra's northernmost glacial basins. For those who are not interested in taking their families on a long, arduous walk, many shorter trails branch from this one and wind up at scenic lakes.

Plumas County Museum, 500 Jackson Street, Quincy, CA 95971. Phone (530) 283-6320. [Fig. 12(8)] Cultural and home art displays are featured, as well as agriculture, mining, logging, and railroad history. Collections include Maidu Indian basketry and pioneer weaponry. The outdoor area has a miner's cabin and mining implements. A carriage and buggy along with a blacksmith shop are also featured.

Historic Coburn-Variel Home, 137 Coburn Street, Quincy, CA 95971, located next to the Plumas County Museum. Phone (530) 283-6320. [Fig. 12(9)] This is a restored, three-story Victorian home furnished from the museum collection.

Portola Railroad Museum, PO Box 608, Portola, CA 96122. Phone (530) 832-4131. [Fig. 13(1)] The Feather River Rail Society established the museum in downtown Portola in 1983 to preserve equipment, photographs, and artifacts of rail travel. During summer, train rides are offered on a 1-mile track.

Indian Valley Museum, Mount Jura Gem and Mineral Society Building, PO Box 165, Taylorsville, CA 95983. Phone (530) 284-6511. The museum, at the corner of Cemetery and Portsmouth roads, features an 1850s to present collection to represent the settling of the Indian and Genesee valleys. There are also mining and mineral displays.

Beckwourth Cabin, 2180 Rocky Point Road, Portola, CA 96122. Phone (530) 832-4888. [Fig. 13(2)] Viewing by appointment only. This is the refurbished hotel and trading post opened by Plumas County pioneer Jim Beckwourth, one of the few pioneer leaders who was African-American.

Read and add comments about this page